Defining Paradigms

What is a paradigm?

They show up in many places as a "crucial concept", but are extremely abstract and difficult to grok.

In today's article, I'll help you understand paradigms by defining their three sub-components. Then I'll use those components to help you understand our current paradigm shift from the Industrial Age to the Information Age.

But first, let's look at how others have defined paradigms.

I. Definitions from Kuhn, Meadows, and Wallace

Thomas Kuhn first introduced the term "paradigm" in his 1962 book, Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Unfortunately, Kuhn didn't define it precisely. The computational linguist Margaret Masterman showed that Kuhn used the word "paradigm" in 21 distinct ways—that's too many! Kuhn gives us the ideas that paradigms are a weird aura that determines how scientists do research. But he doesn't clearly define what that aura is made of.

Then, in 1999, Donella Meadows (of Thinking In Systems fame) explored paradigms in her piece 12 Leverage Points: Places to Intervene in a System. In this piece, she shows how you change a system by doing either "low leverage" activities or "high leverage" activities. The highest leverage activities are changing paradigms.

Leverage Point #2. Changing the paradigm.

Leverage Point #1. The power to transcend paradigms.

Unfortunately, Meadows doesn't clearly define a paradigm. She just says they are "great big unstated assumptions". And then adds this beautiful, but arguably unhelpful, Zen-like reflection on paradigms:

It is to “get” at a gut level the paradigm that there are paradigms, and to see that that itself is a paradigm, and to regard that whole realization as devastatingly funny. It is to let go into Not Knowing, into what the Buddhists call enlightenment.

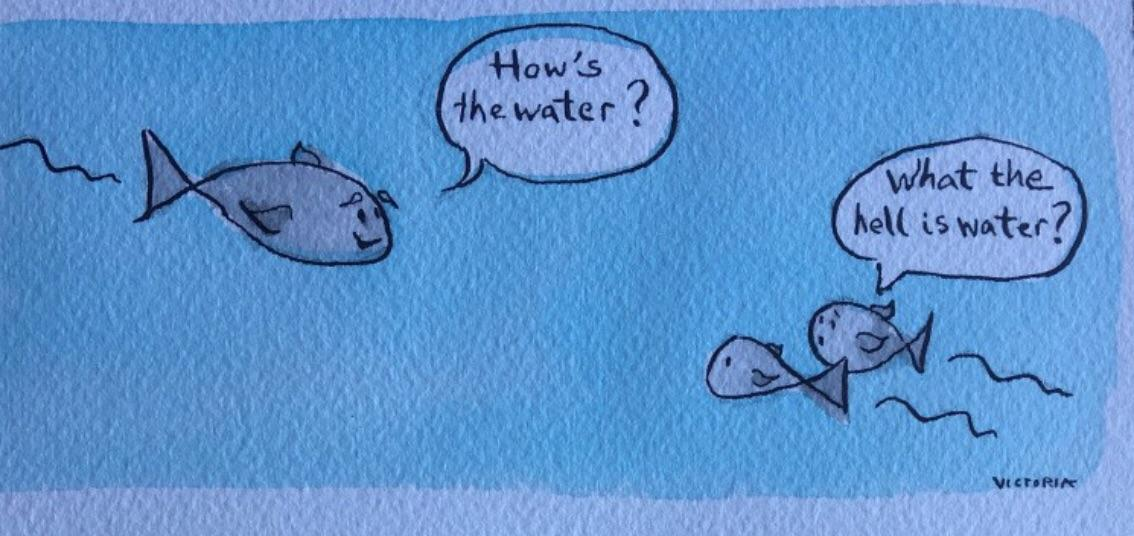

Finally, David Foster Wallace‘s 2005 commencement speech, This is Water, also touches on paradigms. It's the most popular way that people are introduced to the idea.

Wallace begins by explaining the old parable, where one fish asks another "how's the water?"

Paradigms are the water we swim in. As Wallace states:

The point of the fish story is merely that the most obvious, important realities are often the ones that are hardest to see and talk about.

Given this is a commencement speech, Wallace describes the value of education—it allows us to zoom out:

This, I submit, is the freedom of a real education. You get to consciously decide what has meaning and what doesn’t. You get to decide what to worship. That is real freedom. That is being educated, and understanding how to think. The alternative is unconsciousness, the default setting, the rat race.

Still though, Wallace doesn't help us understand what these default settings are.

The core question still exists: What is a paradigm?

II. Paradigms Have Three Parts: Ontology, Epistemology, and Ethics

So we know paradigms are these underlying assumptions / hidden defaults. The water we swim in.

But what is this water composed of? Is it our "values"? Or maybe it's our language? Or perhaps it's our institutions? Are any of those "deep" enough?

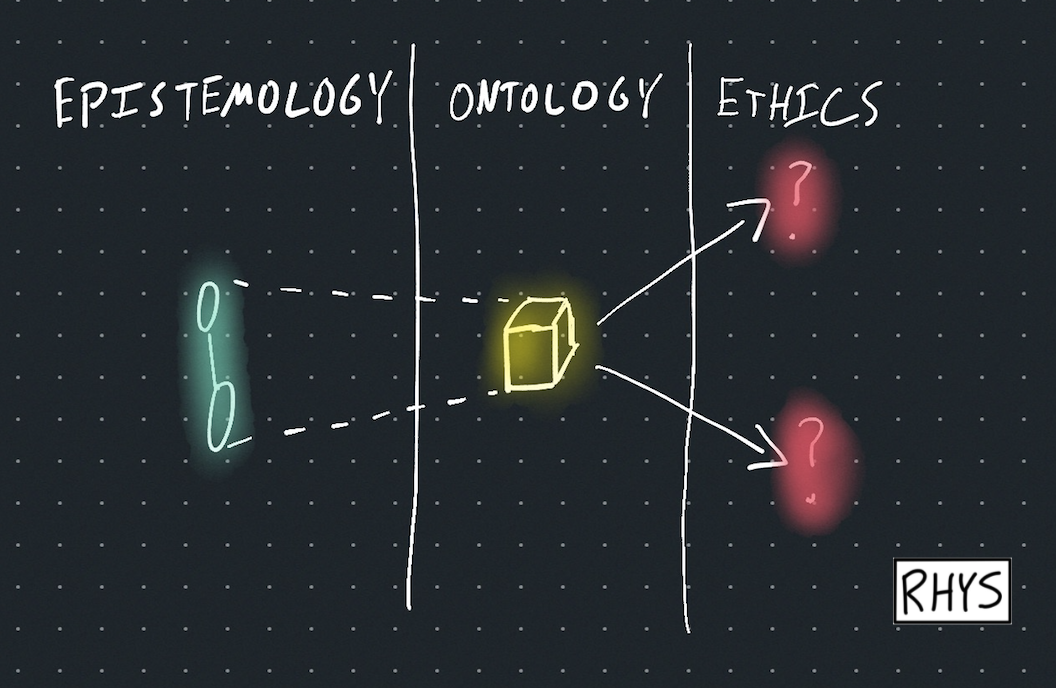

Here's the clearest answer—paradigms are the combination of three orthogonal concepts:

- Ontology: What is true?

- Epistemology: How do we know?

- Ethics: Is it good?

In fact, experts categorize scientific research paradigms by these dimensions. (They ignore ethics, because science is concerned with "is" not "ought".) Here are those three paradigms:

Positivism

- Ontology: The world has a quantifiable truth.

- Epistemology: We can measure it.

Constructivism

- Ontology: Truth is contextual and socially constructed.

- Epistemology: These "truths" become known by understanding individual qualitative experiences.

Pragmatism

- Ontology: Both of the above are true! There are some quantifiable truths and some socially constructed truths.

- Epistemology: Use whatever tool works best! Quantitative measurement or qualitative interviews.

These paradigms aren't purely defined by their (perspective on) ontology or epistemology. Instead, it's the combination of those two things. (With an agnostic perspective on ethics.)

Now let's use this 3D framework to understand the paradigms of society, not just of science. We'll first look at our old Industrial Age paradigm (Capitalism) and then look at our future Information Age paradigm (Post-Capitalism).

III. Society's Paradigm from 1500-2000: Capitalism (Broadcast Factory Liberalism)

What has been the dominant paradigm of society for the last 500 years? Most folks would call it "capitalism". Let's understand it from our 3D perspective: ontology, epistemology, and ethics.

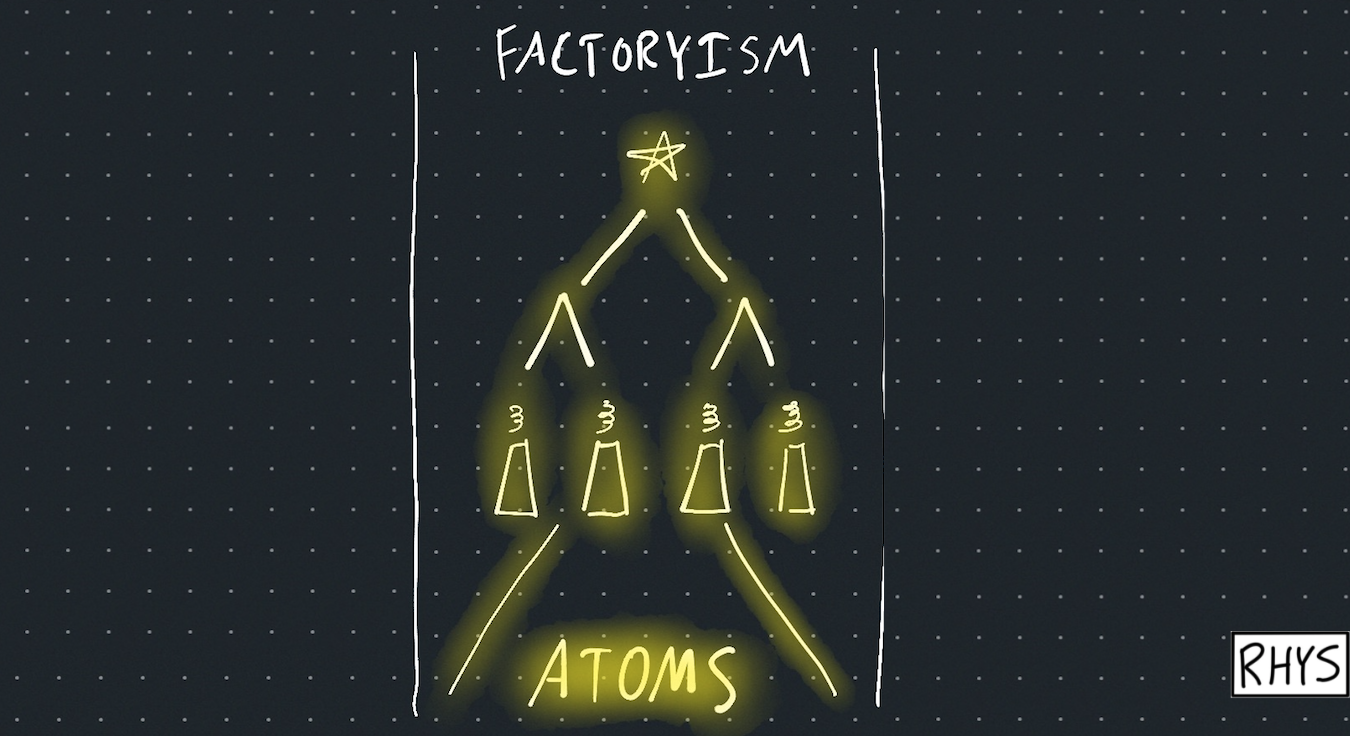

III.A The Ontology of Capitalism: Factoryism

For ontology, we ask "what was happening from 1500-2000?"

We'll use a sociotechnical perspective—how is technology changing society and vice versa?

We could look at a couple of "small" examples like the invention of the cotton gin. But we want to understand this at a macro perspective. To do so, we should borrow two more of Meadows' leverage points: #7—positive feedback loops and #4—self-organizing systems. As a reminder, here is how Meadows defines self-organizing systems:

Self-organization is basically a matter of an evolutionary raw material — a highly variable stock of information from which to select possible patterns — and a means for experimentation, for selecting and testing new patterns.

For technology the raw material is accumulated science. The source of variety is human creativity and the selection mechanism is whatever the market, governments, or foundations will fund—whatever meets human needs.

In other words: new self-organizing systems define a new production function and a way to evaluate who is winning at it. (These are sometimes called "autopoetic" systems.)

We can now add more specificity to our ontological question: what new self-organizing systems exploit/developer the frontier with reinforcing loops to put a massive dent society?

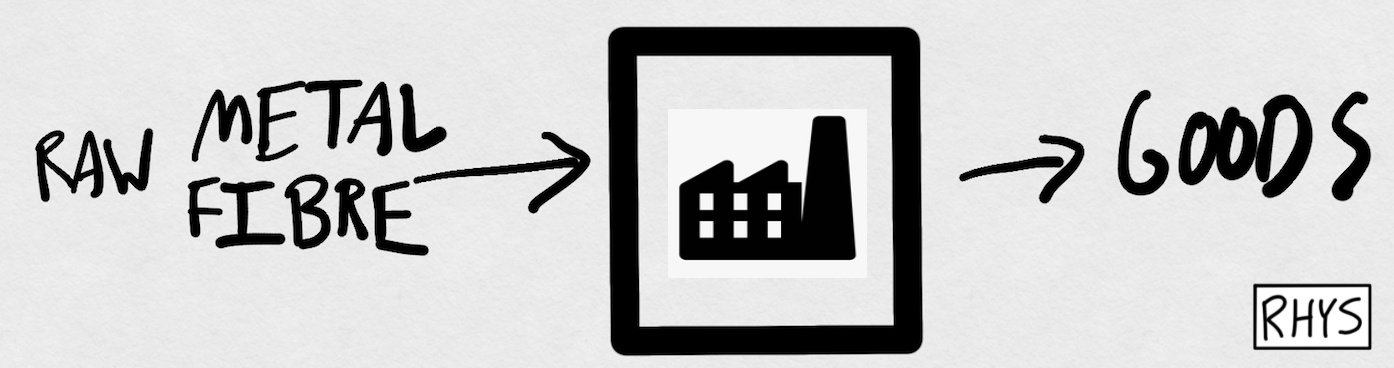

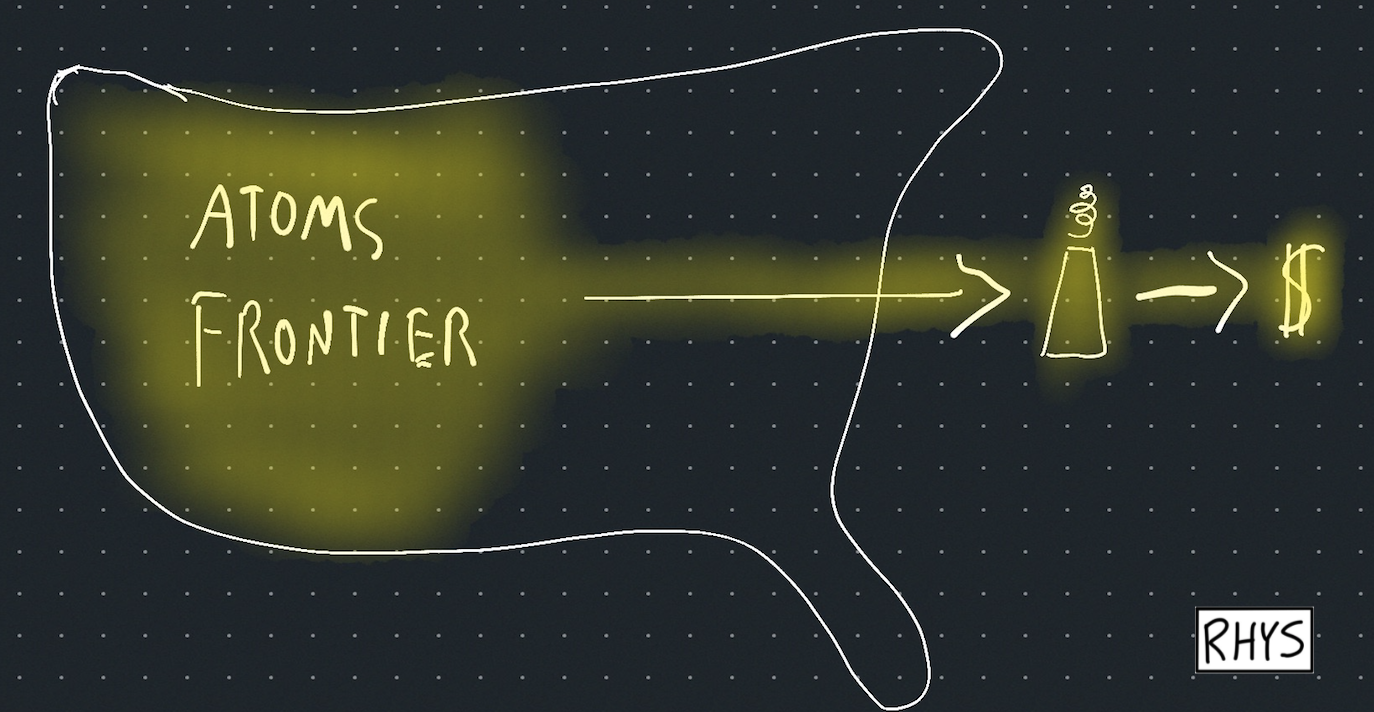

For the Industrial Age, the answer to this is "factories" (combined with the joint stock company). Factories abstracted the process of taking atoms (raw metal/fibre) and turning them into goods:

Company-based factories are a powerful self-organizing system. They take atoms, rearrange them into goods, and then exchange those goods for money.

When a new self-organizing system begins, society is rearranged around it like a vacuum. Factories "suck" all of the atoms towards them. Everyone wants to take atoms, push them through a factory, turn them into goods, and make money.

Self-organizing systems can only survive (and are especially powerful) when the system can perpetuate itself. With biology, the organism needs food/energy to reproduce. With technology, it needs value. Factories need to make money to make more factories.

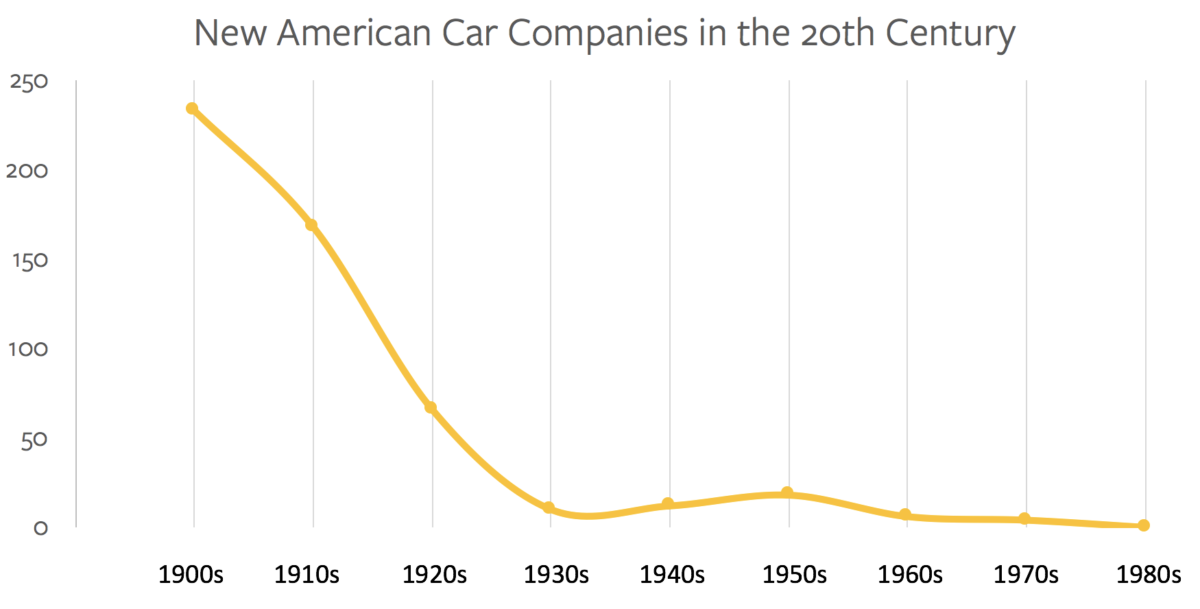

For all tech-based self-organizing systems there are reinforcing feedback loops that create winner-take-all dynamics. This means that there were many car companies when this self-organizing system began, but only a few winners by the end.

And this is because factories are competing (in a new self-organizing system) to turn atoms into money.

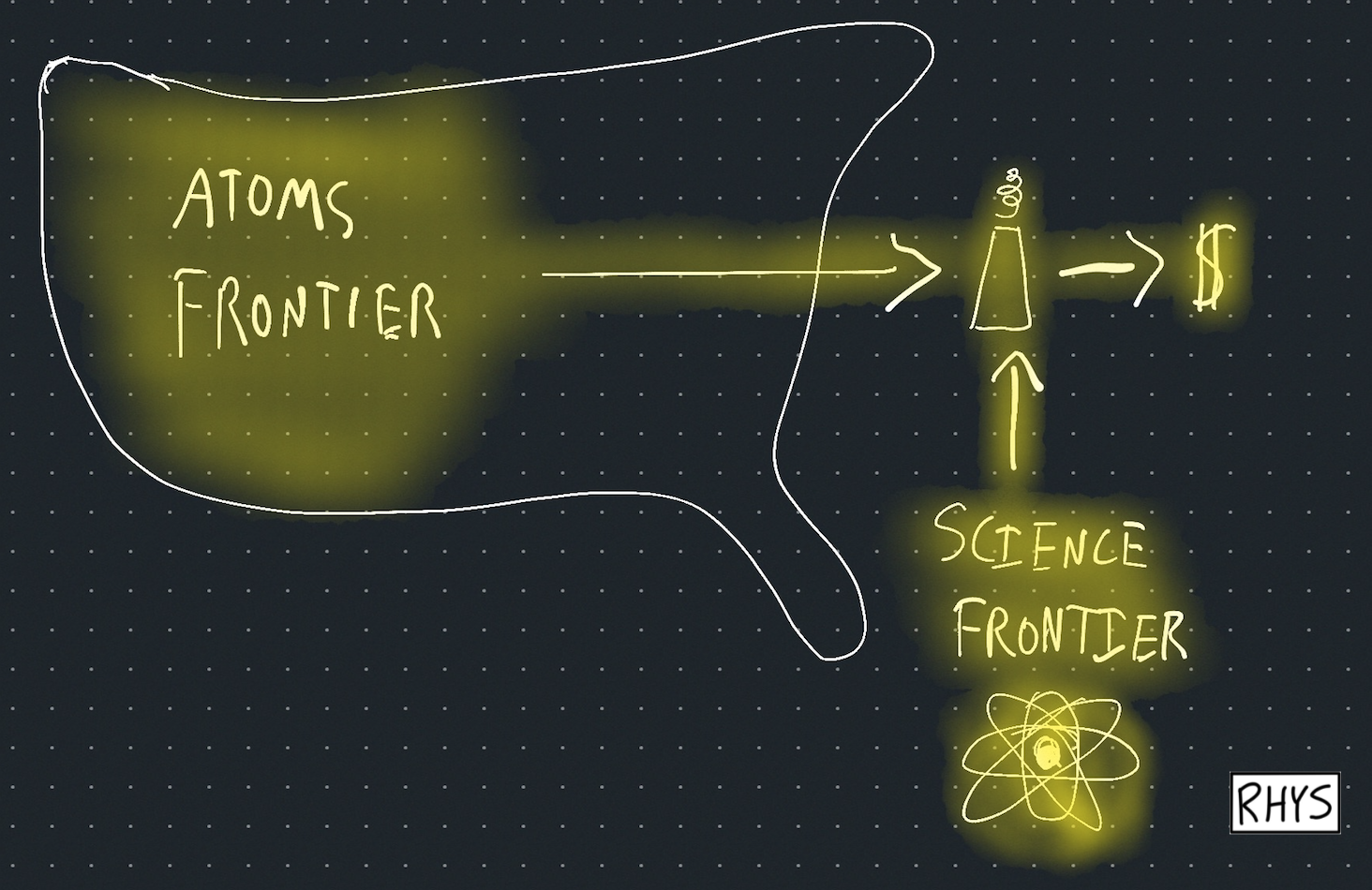

From a "Paul Romer endogenous growth perspective", factories rearrange the atoms on earth to be more "valuable" to humans. This requires two types of frontiers. One is an information frontier: new ideas to turn atoms into goods/value (like the cotton gin). But there's also the physical frontier: society wanted "new land" to find new atoms and turn them into goods/value. This is Manifest Destiny, colonialism, etc.

As the (self-organizing) factory system began to spread, the nation-state began to co-evolve with it (in both a parasitic and symbiotic way). Nation-states created property rights, which were necessary for profit. They created this through a monopoly on violence.

So, roughly speaking, the ontology of the Industrial Age is this—a self-organizing sociotechnical system between Factories and Nation-States. Let's call this Factoryism.

III.B The Epistemology of Capitalism: The Printing Press, Science and Broadcast Truths

Above, we looked at the ontology of capitalism, which is determined by a new self-organizing system that can exploit/develop a frontier and provide value to sustain itself. This perspective is concerned with value. But what of information? This is where epistemology comes in.

Instead of asking "what is happening?", we ask "how do we know what is true, and how does information spread?"

There were three crucial forces here:

- The printing press.

- Science.

- Broadcast media: newspapers, radio, TV

Let's briefly look at each.

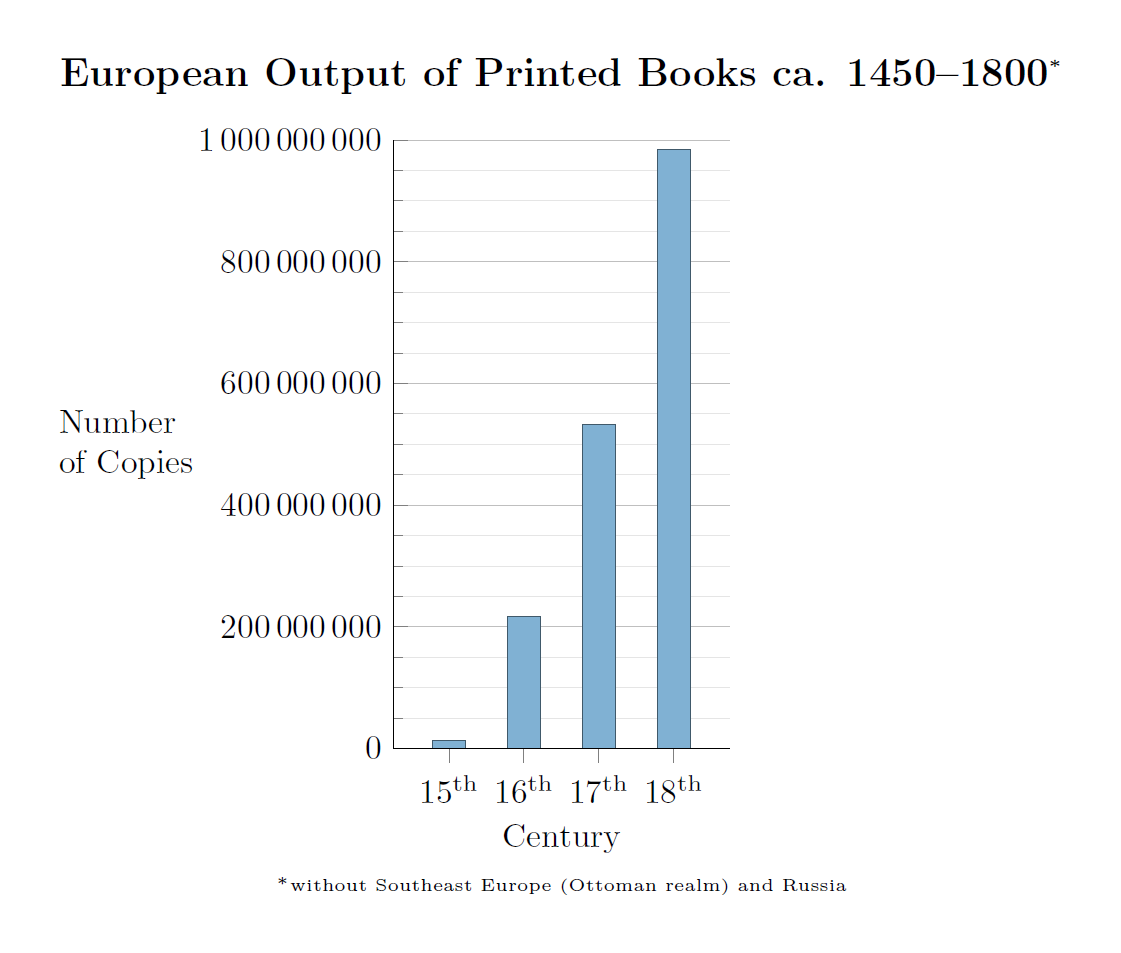

1. The printing press (invented in 1440) changed how information spread. Pre-Industrial Revolution, the church had a monopoly on information because books were expensive to create. The printing press broke this monopoly. Here's how many books were created after the invention of the printing press:

With that monopoly broken, the word of god could be undermined, creating competition among Catholic and Protestant religions. (Luther’s works accounted for 33% of all German-language books sold between 1518–1525!)

The printing press broke an epistemological monopoly on "what is true?" (science) and "what is good?" (Protestantism).

2. Science grew out of the printing press. The scientific method (as we now know it) was cultivated throughout the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment (~1550-1800). It changed how we determined truth. Instead of accepting religious text, we tried to determine (through experimentation) what was true. This was a crucial input for the Factory Loop above. By "mining"/"exploring" the scientific frontier, we were able to find new knowledge that would allow us to convert atoms to goods and make money. We might call this "innovation" or "R&D".

3. Later on, broadcast media also influenced our sense of "what is true?" This allowed nation-states to provide a clear, 1D version of truth—a strong nationalistic narrative for citizens to abide by. They could blast this truth out through newspapers, radio, and TV.

To conclude, the Industrial Age changed our epistemology. The printing press broke the Catholic Church's monopoly on "what is good". The scientific method allowed us to determine "what is true" and use that as an input for factories to make money. Later, broadcast media allowed the winners of the Industrial Age (nation-states) to produce 1D narratives for their citizens.

III.C The Ethics of Capitalism: Liberalism

We now know capitalism's sociotechnical ontology (the factory loop) and epistemology (scientific method and broadcast media). What are capitalism's ethics? What does capitalism see as "good"?

Roughly speaking, capitalism's ethic is liberalism (not to be confused with capital-L Liberals). If you ask liberalism, "what is good?", it responds with something like "rule of law and individual rights to life/liberty/property." Liberalism defines the individual's relationship to the state—the "social contract". This contract is this—the state provides the rule of law + rights, and the individual provides hard work + taxes.

This "Protestant work ethic" (pushed by a moralizing god) fuels capitalism. As Adam Smith wrote: "It is not from the benevolence of the butcher that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest." Or, as Hirschman synthesizes in Passions and Interests, capitalism harnesses our negative passions for our long-term interest. The factories need input, and liberalism provides the labor for them.

In addition, the Industrial Age had ethics based on self vs. other. Slaves, indigenous people, Jews, and others could be defined as "other". We are good. They are bad. This was another way to justify and create the labor needed for factory inputs.

This form of "othering individualism" has reached its peak at the end of the 20th century, with statements like this from Milton Friedman—"The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase its Profits."

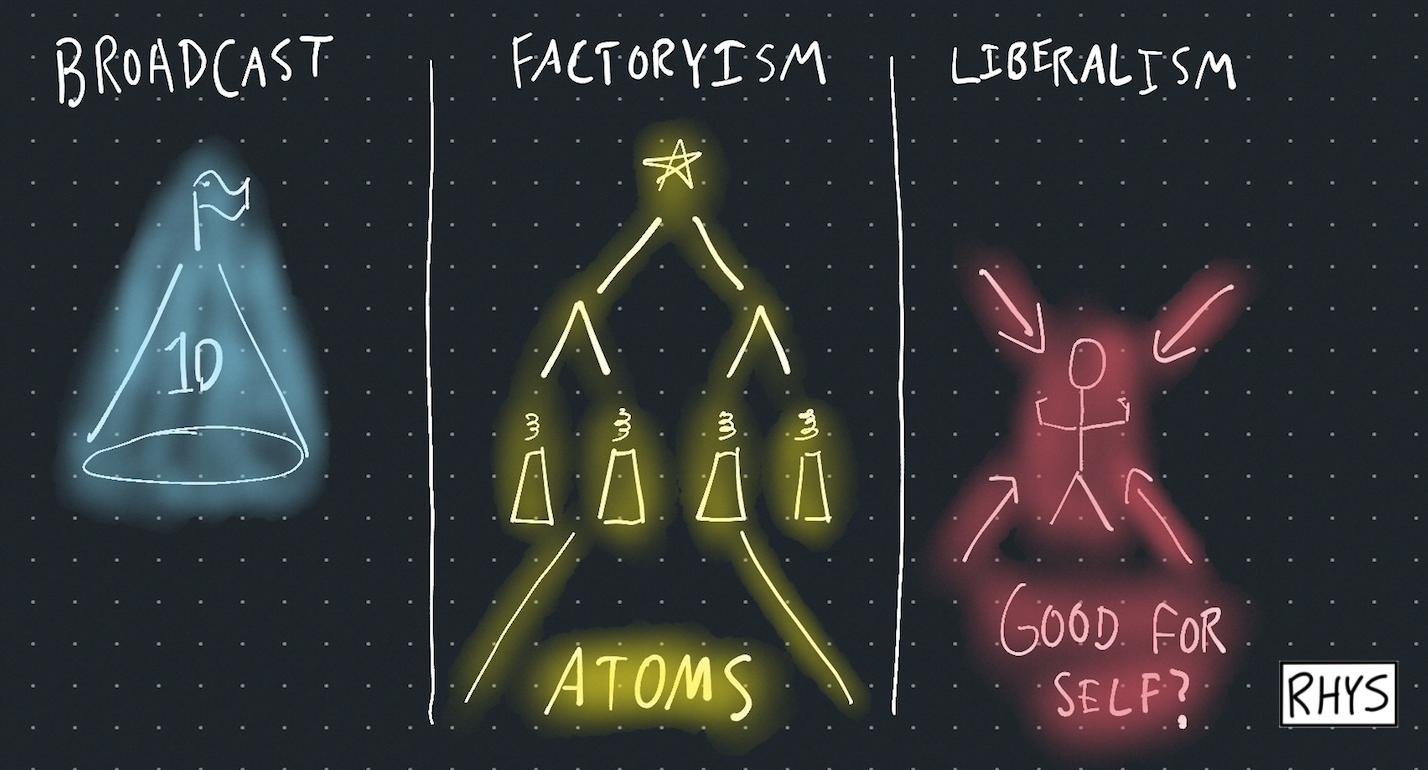

So this was the paradigm of capitalism:

- Ontology: Factoryism—Self-organizing + reinforcing system that feeds itself by turning the atom frontier into valuable goods.

- Epistemology: Broadcast—1D narratives create coherence.

- Ethics: Liberalism—An "othering individualism" that says what's best for you is best for the collective.

Each of these reinforces the other. For example, science and liberalism provide inputs for the factory's to produce value. In fact, they need to reinforce each other. You can't compete if you're not aligned with the most powerful reinforcing loops.

Let's now look at society's paradigm going forwards into the Information Age—post-capitalism.

IV. Society's Paradigm from 2000-2500: Post-Capitalism (Networked Plural Bentoism)

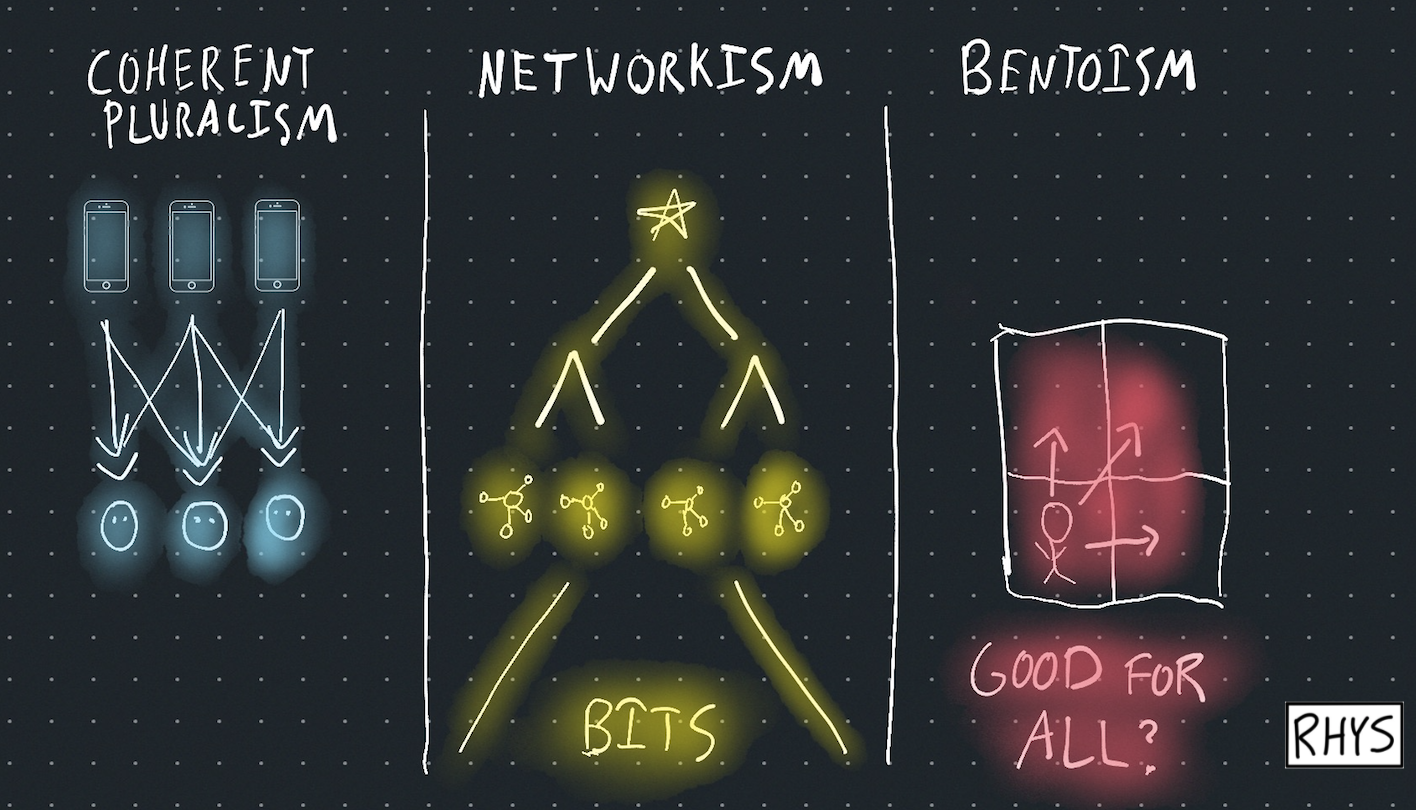

Capitalism is in crisis. Our society is shifting towards our next paradigm, which I'll call "post-capitalism". This paradigm has three components:

- Ontology: Networkism—Self-organizing + reinforcing system that feeds itself by turning the bits frontier into valuable knowledge.

- Epistemology: Coherent Pluralism—Individuals taking many perspectives into account, while still striving for clarity.

- Ethics: Bentoism—Zooming out to an active awareness of your impact on others and the future.

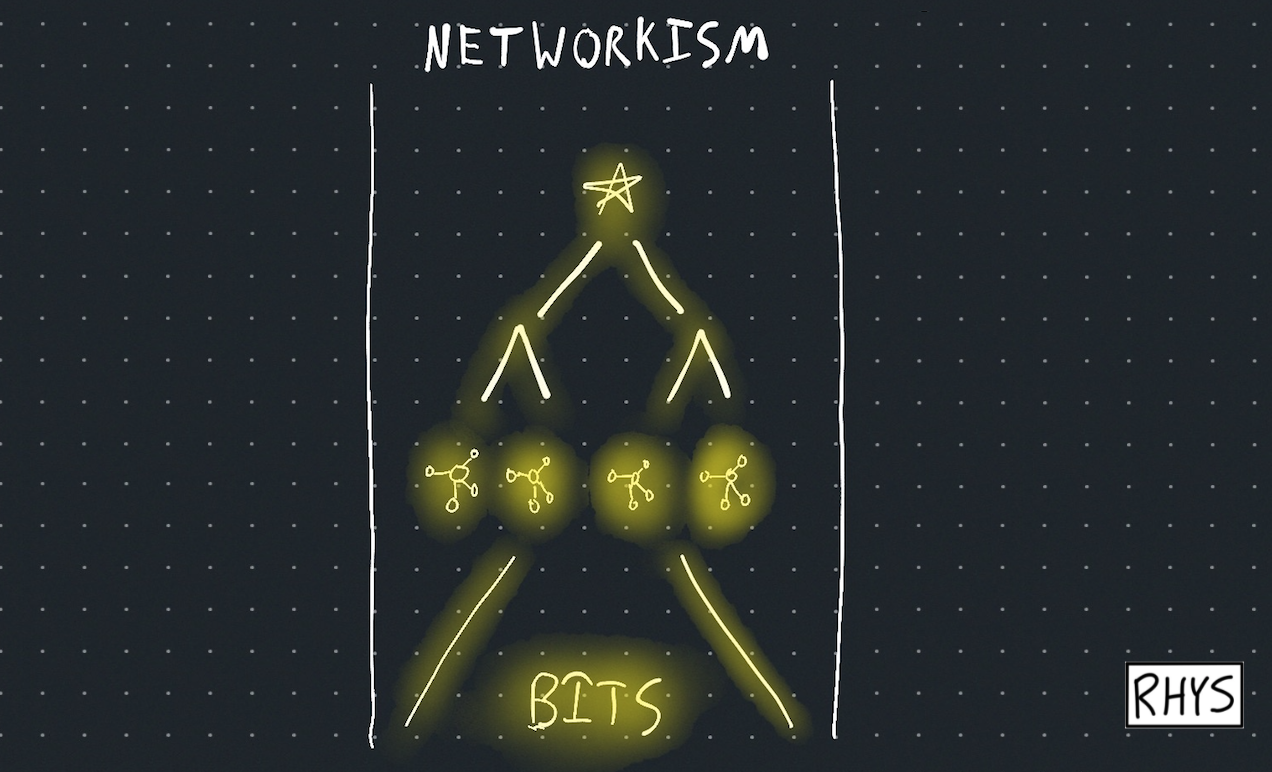

IV.A Post-Capitalism's Ontology: Networkism

Again, the ontological question to ask is: what new self-organizing systems exploit/develop the frontier with reinforcing loops to put a massive dent society?

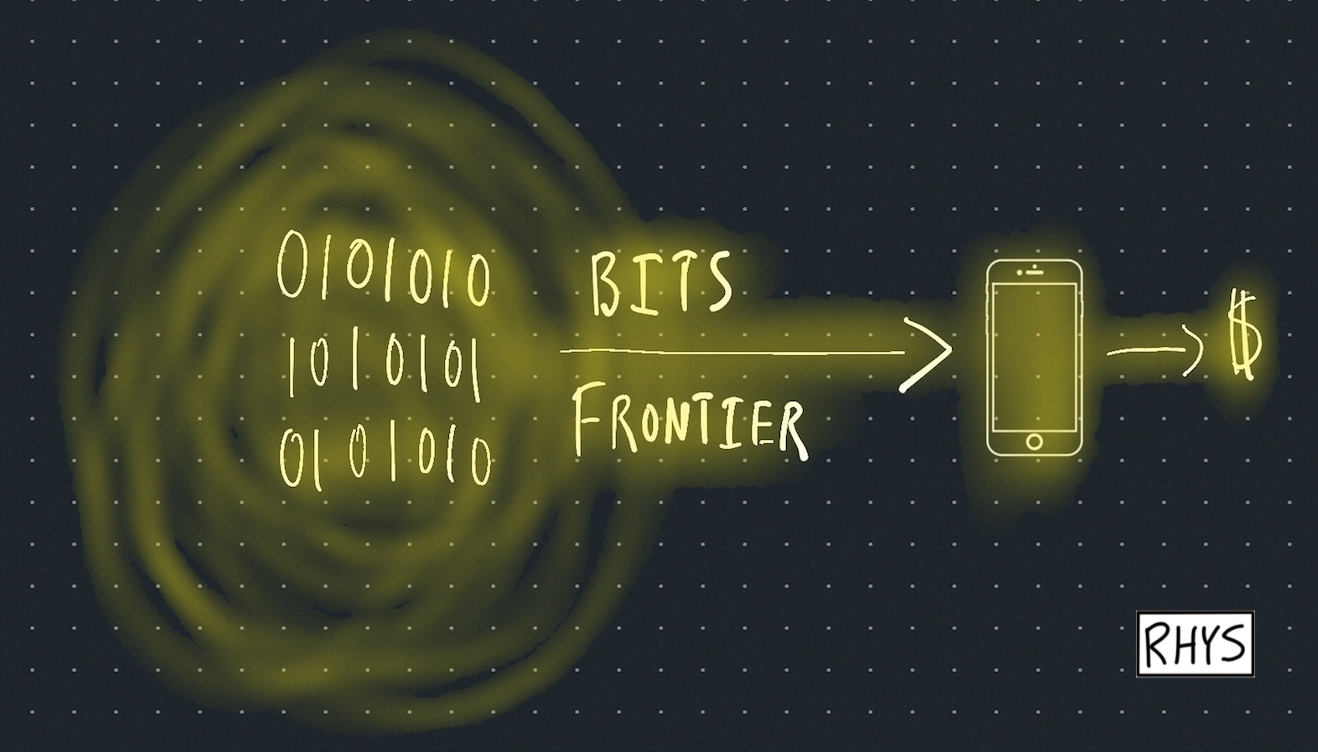

From 1950 onwards, the frontier has been in the land of bits, not atoms. There was an immense amount of untapped value for companies to create hardware (computers), software (operating systems), and networks (the internet).

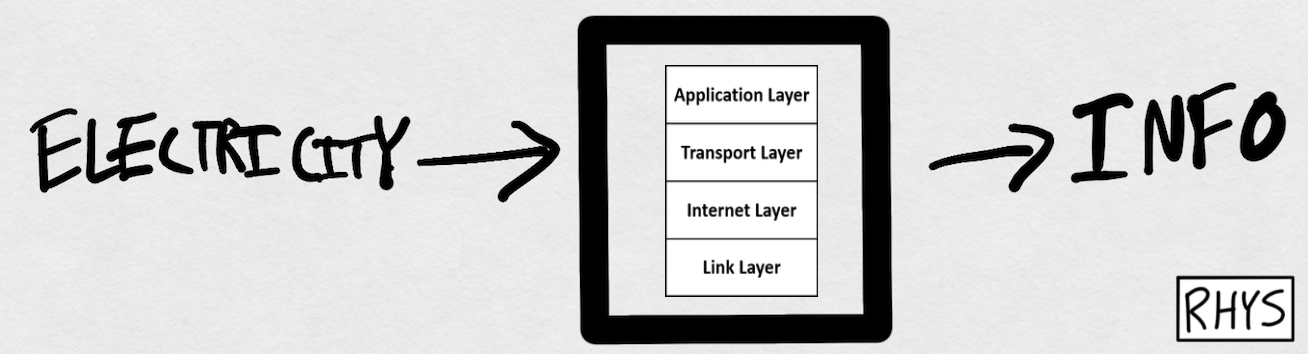

Just as factories abstracted a process that turned atoms into goods/value, so too did internet protocols abstract a process for turning electricity/bits into information/value.

And, like with factories, this new abstraction created a self-organizing system of competition, where fitness was again determined by what could be monetized (often attention). Let a thousand flowers bloom!

And like with factories, low-friction protocols create reinforcing feedback loops that lead to winner-take-all dynamics (i.e. Aggregation Theory).

Networkism is post-capitalism's ontology. Bits are the valuable frontier that drives the value loops in society.

What then is our epistemology? How do we determine what is true and what is good?

IV.B Post-Capitalism's Epistemology: Coherent Pluralism

The printing press democratized the written word in 1440 to breakdown gatekeepers and allow for competition of truth (science) and goodness (Protestantism). We see a similar shift with the internet today—removing gatekeepers to create competition of truth and goodness. We no longer just have broadcasting, but have personalized narrowcasting as well (our feed).

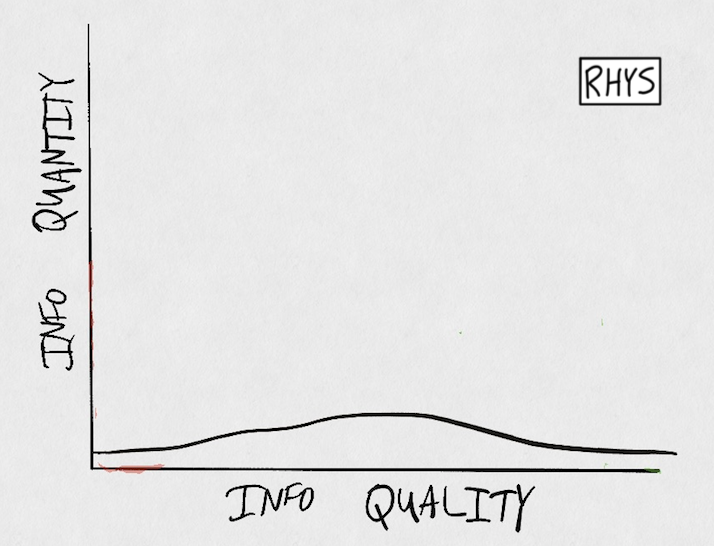

By allowing for zero-cost distribution of information to four billion networked smartphones, the internet has drastically increased our amount of information. We went from a small amount of (broadcasted) info, most of which was of ok quality:

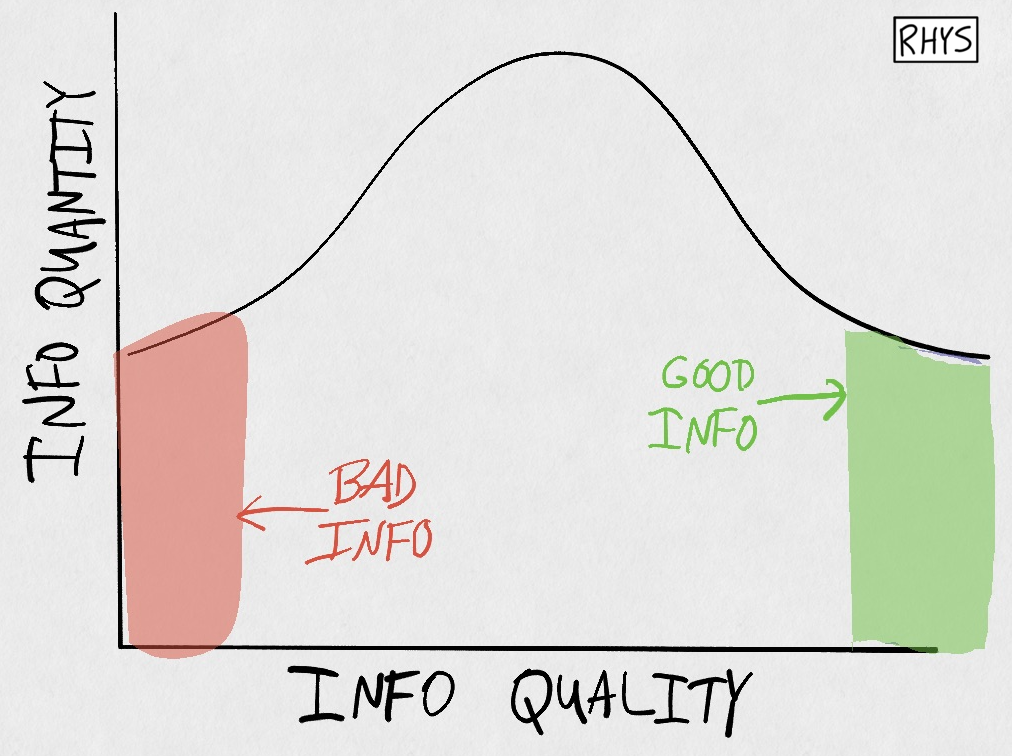

To an abundance of information, some of which is good, and some of which is bad.

This is where the concept of "post-truth" and "fake news" come from. If there's so much info, and a diminishing of trusted gatekeepers, it's difficult to determine truth and "real news."

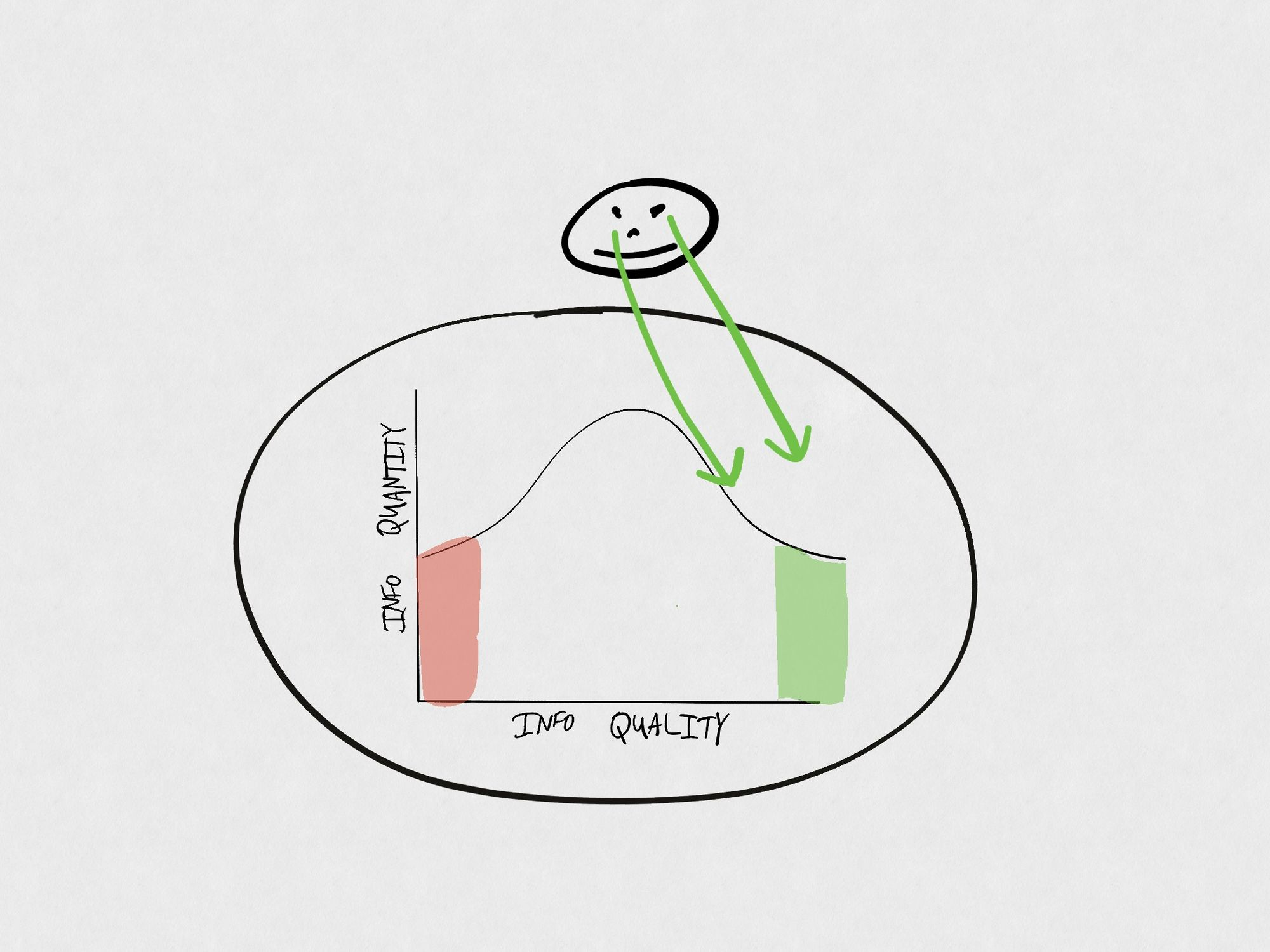

In this networked sensemaking environment, individuals must take individual responsibility for their own sensemaking. We call this Coherent Pluralism—looking at lots of perspectives (Pluralism), while also creating clarity among them (Coherence). Individual must look at the firehose of info and search for the best:

We no longer have the broadcasted, 1D coherence given to us by nation-states/radio/TV. That would be Coherence without Pluralism. But we can't just look at the abundance of info and say "fake news". That would be Pluralism without Coherence. Instead, individuals need to take responsibility over their own epistemology, and the resulting collective emergent epistemology, with a mindset of Coherent Pluralism.

Coherent Pluralism is our epistemology give that our ontology is Networkism.

IV.C Post-Capitalism's Ethics: Bentoism

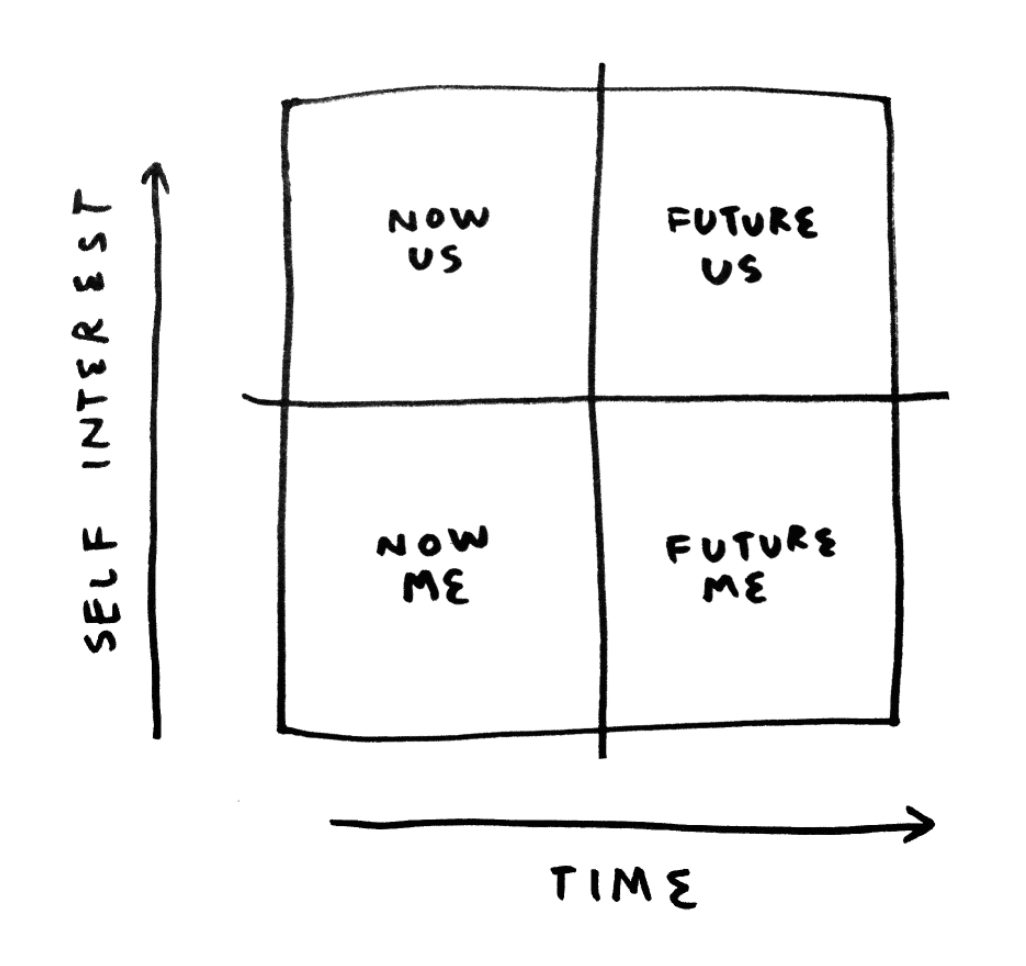

Finally, what are the ethics of post-capitalism? In post-capitalism, what is good? My favorite way to understand this is through Yancey Strickler's simple 2x2, Bentoism.

It allows us to understand our societal needs: Now Me basic needs, Future Me meaning needs, Now Us connection needs, and Future Us sustainability needs.

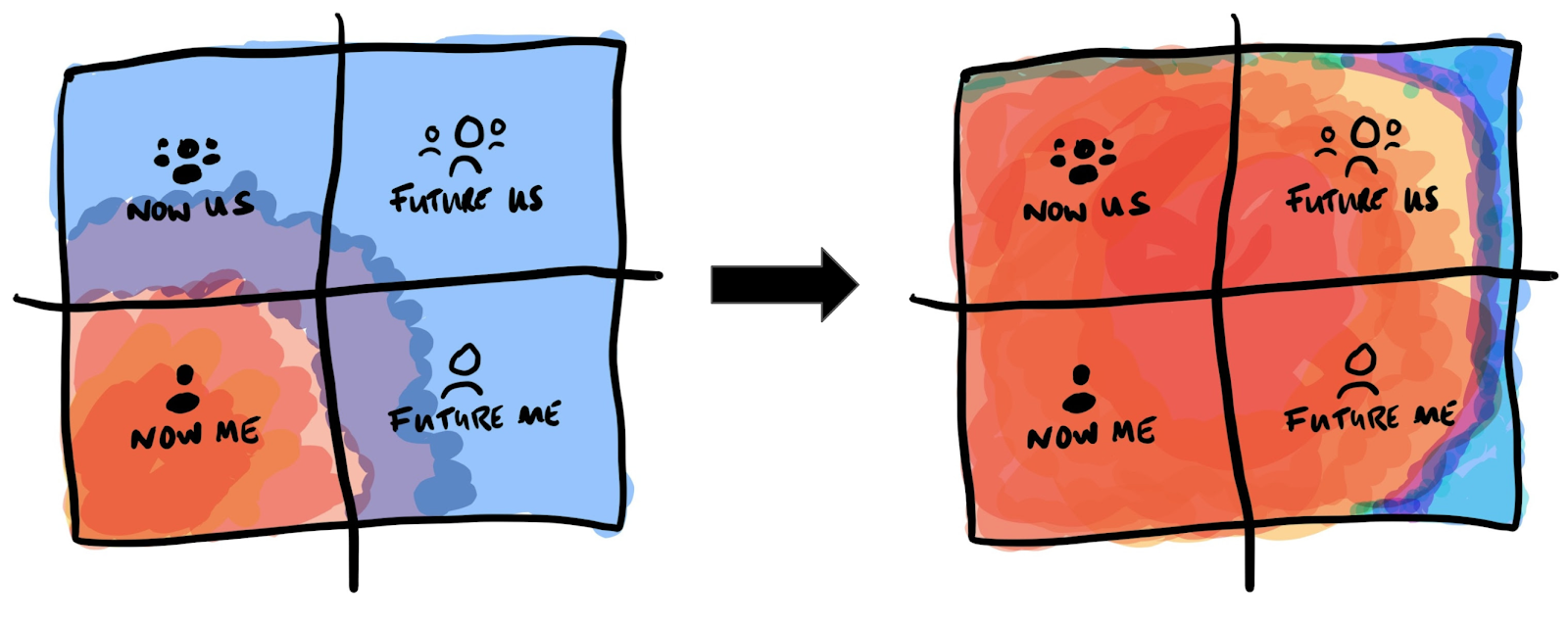

It is a mirror which reveals that we've been too focused on Now Me needs, and should zoom out to a more holistic perspective:

Instead of capitalism's ethics—"Othering Individualism"—we have post-capitalism's ethics—"Connected Collectivism."

In the age of climate change, hyperconnectedness, and the abundance of capital, a purely self-motivated ethic no longer works.

So this is the paradigm of post-capitalism:

- Ontology: Networkism—Self-organizing + reinforcing system that feeds itself by turning the bits frontier into valuable knowledge.

- Epistemology: Coherent Pluralism—Taking many perspectives into account, while striving for clarity.

- Ethics: Bentoism—Zooming out to an active awareness of your impact on others and the future.

As with the Capitalist paradigms, each of these Post-Capitalist pieces reinforces the other. For example:

- Coherent Pluralism is a strong epistemology because of Networkism.

- Bentoism is an example of Coherent Pluralism (it is a plural yet coherent framework).

- The strongest networks take the whole Bento Box into account (stakeholder capitalism).

In fact, they need to reinforce each other. You can't compete if you're not aligned with the most powerful reinforcing loops.

V. How Do The Paradigms Relate to Each Other?

Now that we've looked at each paradigm, let's explore how they relate to each other.

The Two Paradigms are Incommensurable

Kuhn says that paradigms are "incommensurable" to each other. This means that you can't directly compare them to each other. The underlying concepts and language are just too different, so they end up "speaking past" each other.

This is true with the Capitalist vs. Post-Capitalist paradigms as well. For example, from the perspective of a liberal Othering Individualist, zooming out to care about Future Me, Now Us, or Future Us is irrational. Rational decisions are those that maximize quarterly earnings, or increase your own wealth (not ones that take Future Us into account).

The Post-Capitalist Paradigm is a Superset of the Capitalist Paradigm

There's another way to view their relationship. Instead of capitalism and post-capitalism being completely disjoint sets (a venn diagram with no middle), you can think of post-capitalism as a superset of capitalism.

- Bentoism: Instead of viewing ethics from a 1D Now Me perspective, we zoom out to a 4D Bento Box perspective. It's the same as before, just more.

- Coherent Pluralism: Instead of doing epistemology through 1D broadcast narratives, we both have 1D broadcast narratives and bottom-up nD pluralism. We get to "choose both."

- Networkism: Wal-Mart with a website is strictly better than Wal-Mart without a website. All of the same "old businesses" are possible, but now can have an additional digital layer. (In addition to the whole set of new businesses that are network-first, e.g. Uber.)

Combining incommensurability and superset-ness, we can see why post-capitalism will succeed. In order to outcompete the existing capitalist paradigm, you need to both:

- Compete on an orthogonal axis. (Be incommensurable with it. i.e. Look irrational.)

- Outcompete it on it's own terms. (Be a superset of it.)

What Hidden Assumptions are Changing?

Let's return to paradigm definitions from Kuhn, Meadows, and Wallace. They don't mention ontology, epistemology, or ethics. Instead, they focus primarily on "hidden assumptions." So what hidden assumptions are changing? How is the "water we swim in" changing?

- Ontology: We're switching from exploiting/developing the atom frontier to the bits frontier. With this comes the decline in centralized institutions and the rise of decentralized networked institutions.

- Epistemology: We're transitioning to an understanding of the world that takes "a flood of internet information" as a given. Individuals will learn to swim uncertainty.

- Ethics: We're transitioning to a view of humanity as a bottom-up network. We're starting to see that we're all connected and that our actions impact the rest of the hive.

I hope this helps you understand how paradigms operate. Thanks for reading and let me know if you have any questions/comments!

Notes

Research Paradigms

- These research paradigms map well onto modernism (one truth), post-modernism (infinite truths), and meta-modernism (many truths, choose a couple).

- Technically, ethics is not the highest meta category for "what is good?" Instead, there's a category called "axiology", which contains both ethics (what human actions are good?) and aesthetics (what objects are good/beautiful?).

- This points towards an idea that ethical systems compete on meaning. e.g. Ethical systems are often tied to meaning-based systems (religion). Bentoism (and new ethical systems) need to compete on meaning. Effective Altruism does a pretty poor job of this.

- In theory, science is apolitical, without ethics. But it's becoming increasingly political. (See epidemiologist's statements on Floyd protests.)

- There are programming paradigms as well. Imperative (procedural) vs. declarative (functional) languages. Each have their own ontology, epistemology, and ethics (no side effects!).

Capitalism

- With factories, one of the most powerful loops is "Wright's Law" (named after the Wright Brothers), which states that for every doubling of production, there will be a constant decrease in price per unit. We can see this clearly with Model T's. In 1909, Ford produced 10,000 cars at a cost of $25,000/car. By 1925, they made 2,000,000 cars at $4,000/car. In 15 years, they produced 200x cars at 10% the price.

- The monopoly on violence was created by its own reinforcing feedback loop: the Gunpower Revolution and increasing returns on violence. (If you're a bigger nation-state, you can steal more land, producing more goods, which help you take more land.) In other words: “The nation-state facilitated systematic, territorially-based predation.”

- My historical account takes a super western/European perspective. What was happening around the world? I don't know nearly enough here. (Though, AFACIT, the Industrial Revolution was centered around the UK and the US.)

- I don't mention it, but there was lots of institutional competition. The constellation of capitalism, liberalism, and Christianity were not inevitable winners from the start. Instead, they competed with other institutions (like communism) over axes like meaning and money.

Post-Capitalism

- In my Marriage Counseling with Capitalism piece, I show 4 pieces of post-capitalism, not just 3. The 4th idea is "Generosity / Abundance". It's pretty crucial for the transition too. Part of it is ontological—individuals are experiencing an abundance of money (after 45k/year). The "abundance" part is ontological too—it's details the process from abstraction to abundance. In Networkism, I mostly talk about abundance of info, but this is happening with trust and money as well. The "Generosity" part of this idea is ethical. It says "if you have Now Me Overflow, give to Now Us and Future Us." This overflow gives us slack to outcompete capitalism.

- Fwiw, I think we also saw a shift in science-based epistemology towards complex systems and data modeling. i.e. Modeling as a substitute for experimentation.

- I talk about the monopoly winners of the internet (GAFA). But it also enabled long-tail of businesses that build on protocols/platforms.

- In addition to Coherent Pluralism, we need to use Libertarian Paternalism to shape our sensemaking ecosystem towards good/true things. See https://www.rhyslindmark.com/content/images/2020/04/image-12.png and https://www.rhyslindmark.com/defining-abundance/

- There's a juicy intersection between Networkism and ethics. i.e. What is good is just "what gets clicks".

- Again, I'm not sure there's a better name for this new paradigm. Post-capitalism feels fine, but not great. (It's defined as post-X rather than the thing in and of itself!)

- Related: I could see how one would read this article and be convinced that I was a Marxist communist. I'm not! I'm a big fan of markets. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

- One way to see the shift of frontier from atoms to bits is by looking at workers across farming, blue collar, and white collar. Farming goes down, white collar goes up. Related: tech (in isolation) is 5% of GDP and 3% of employment.

- Where is AI? Networkism downplays AI. Part of this is my own bias. Part of it is trying to understand how humanity co-evolves with tech. And I think viewing us as a networked human organism (interacting with networked code/AI) is powerful.

Other

- What is the next frontier? I explore this a bit in my piece here: Building Paradigms. The classic answer is something like: schools, healthcare, and housing. I mostly agree with that. How can we funnel money from bits to atoms? Also, I think that developing new rules for self-organizing systems is key. We know that VOIP and video calling are an inevitable arrangement of bits. To serve everyone the best, do we need 20+ companies developing competing approaches? As Meadows wrote to develop "marvelously clever rules for self-organization."

- There are some issues with how we've developed/exploited the bits frontier. In the US, we took (from native folks) the Western frontier and gave it to the public (with the Homestead Act and Land Grants for universities). But value from the bits frontier has mostly been captured by the elite.

- There's an interesting intersection between Ethics and autopoietic systems. "What is valuable" from an ethics perspective determines how the autopoietic system feeds itself.

- Ethics is the underlying foundation behind values and goals. Values/goals are means to get to an ethics-based end.

- I understand that I'm claiming an ontology here (based on an underlying epistemology and ethical framework). i.e. Saying "paradigms are composed of ontologies, epistemologies, and ethics" is an ontology in an of itself. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

- Our current ontological truth can be represented as the current structure of atoms and bits. (i.e. The state of all atoms and bits at t = now.) Though I find it more powerful to define and ontological truth as the underlying autopoietic system, because it shows what will happen in the future.

- "The basic mistake is that we've invented this wonderful system of language and calculation. It is at once too simple to deal with the complexity of the world and also that we are liable to confuse that system of symbols with the world itself." — Alan Watts

- When I was doing research for this piece, I took a rather meandering path (as shown by my Roam here). My goal was to synthesize the Values Stack with Brand's Pace Layering with Meadows' 12 Leverage Points with Lessig's dot. This led down a path of differentiating values vs. ethics vs. needs. The key (re)learning here is the World Values Survey. And, of course, looking at language as well. Down the Sapir-Whorf rabbit hole again.

- "Paradigms as language" is a pretty strong take. Language is a great way to understand your ontology, epistemology, and ethics. We can see this in recent word of the years. Networkism: 😂, post-truth, fake news, misinformation, echo chamber, gif, selfie, #MeToo, #BlackLivesMatter, infovore, deepfake, influencer, gig/sharing economy. Coherent Pluralism: they, non-binary, gender-fluid, my pronouns. Bentoism/Future Us: climate emergency, climate strike, existential.

- There's also the "paradigms as metaphor" perspective. What metaphors do we use in society, and how do they change our perceptions/reality? e.g. Thinking of humanity as a machine, or a computer, or (now) an organism. Also see how something like Fordism was injected into our schools (school as factory).