The WEIRDest People in the World

The cultural evolution of psychology is the dark matter that flows behind the scenes throughout history.

Joseph Henrich is the world's leading scholar of cultural evolution. He released a brilliant book last week, The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous.

The book starts from this question: Why are Western folks psychologically different than other people around the world?

This Western peculiarity was found after scientists realized that many of their research subjects were homogenous: Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Developed. Henrich calls these folks "WEIRD". Psychologically speaking, WEIRD folks are especially individualistic and analytical. In contrast, non-WEIRD folks (from Asia or the Amazon) are more collectivist and holistic.

Henrich asks the question: Why are WEIRD folks so peculiar? And how has this WEIRDness made the West so prosperous?

He tackles this question by exploring the co-evolutionary process between genetics, biology, psychology, norms, and institutions. Henrich looks at how these processes co-evolve through time: from apes, to early homo sapiens, kin-based structures in the Agrarian Age, the Catholic church in the Middle Ages, the Protestant Reformation, the Industrial Revolution, and finally to the modern institutions of our modern era.

Let’s start by giving an overview of Henrich's model—how genetics, biology, psychology, norms, and institutions co-evolve.

I. Systemic Evolution

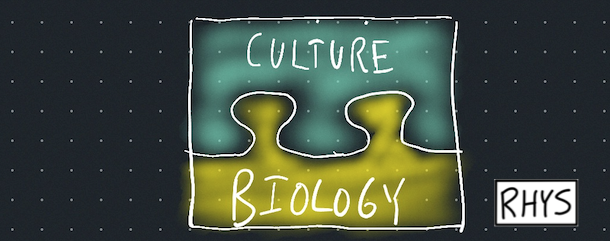

Systemic evolution (my term, not Henrich's) is the co-evolutionary process outlined above—how biology co-evolves with culture. It is the unique lens that cultural evolution provides as an academic field. For a simple example of this lens, let's consider how our genes have co-evolved with our culture.

Why do folks in Nordic countries have blue eyes? First, early homo sapiens had to survive in the cold north. To do so, we developed the technology to farm cereal. This allowed us to move north and still eat. But the north doesn't have much sun, which means we get less Vitamin D and don't need to worry as much about UV skin damage. So then we started to produce less melanin and our skin got whiter. As part of this, one of our melanin-producing genes had a mutation which made it produce less melanin. This made our skin whiter. And coincidentally, that "skin color" gene was close to our "eye color" gene, and so we got blue eyes!

Before humanity developed farming technology, all of us had brown eyes. Then we developed an adaptation at the cultural level (farming), which changed us at the genetic level (blue eyes). This example of culture-gene co-evolution points to the essence of systemic evolution—that our biology evolves as our society evolves.

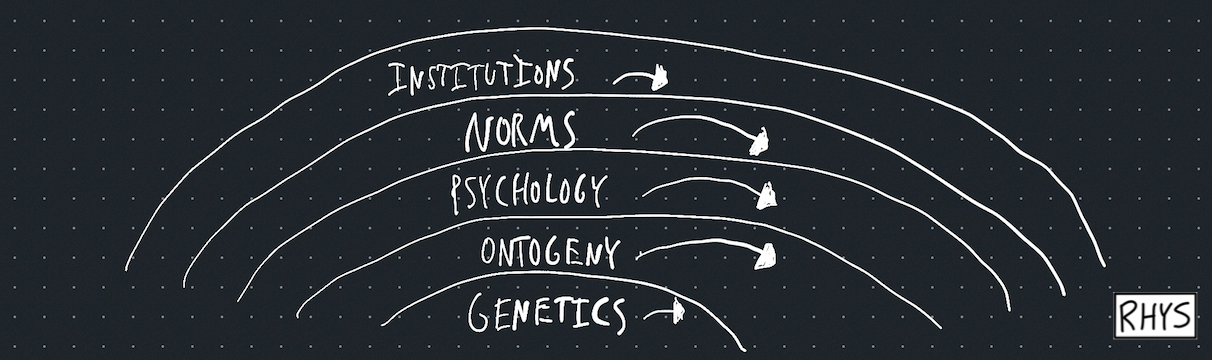

There are five levels of systemic evolution: genetics, ontogeny, psychology, norms, and institutions.

- Genetics: Genetic evolution happens slowly on generational time-scales of thousands of years. "Fitness" is determined by what genes reproduce the most.

- Ontogeny: Ontogeny refers to the physical development of an organism during its own lifetime while genetics (or phylogeny) refers to how the organisms have evolved across lifetimes. As an example, taxi drivers have highly developed hippocampi, the part of the brain responsible for navigation.

- Psychology: Psychology is how our brains process information. As opposed to the levels above, which are purely biological, psychology is more culturally-focused. As an example, WEIRD societies are individualistic, while non-WEIRD societies are collectivist.

- Norms: Norms are what happens when we project our inner psychology out into the world. It is the praise we receive for jumpstarting a neighbor's car. Or the shame when someone steals a bike. These norms can become moderately calcified into habitual actions like shaking hands to greet each other.

- Institutions: Institutions are the formalization of norms into even more calcified structures like laws, markets, corporations, and nation-states. These institutions are usually written down and change more slowly.

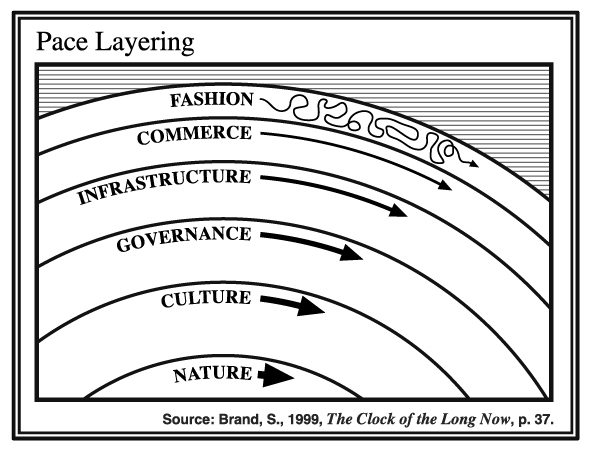

I like to think of these levels like Stewart Brand's pace layers—they move at different time scales. Here's Brand's pace layering:

And here's Systemic Evolution, which moves in a slow-fast-slow pattern:

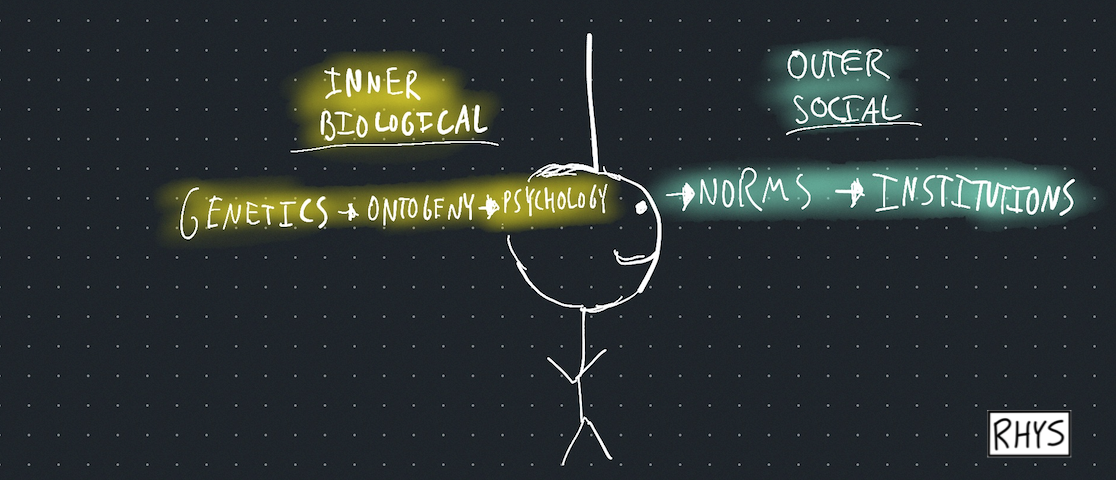

In addition, System Evolution moves from the inner biological world, to the outer social world:

How can we understand the evolution of these layers? To do this, we need to understand the how higher cultural layers in the evolutionary stack "fit" onto lower down biological anchors.

II. Biological-Cultural Fit

Biological-cultural fit is the extent to which cultural adaptations fit onto our biological anchors. For example, we can't make biological ants believe in a Sun God. Ants' simple biology isn't a good anchor a complex culture.

For another example, let's look at how our cultural marriage norms were built on our biological pair-bonding instincts. As homo sapiens moved away from apes, we developed pair-bonding instincts to have a male-female pair watch over their children as their brains developed. From that biological instinct (pair-bonding), we developed the cultural technology to create marriage norms like wedding vows. But if we didn't have our pair-bonding anchor, those marriage norms wouldn't have stuck. Imagine trying to get sex-happy polygynous bonobos to settle down with one partner for life!

We can only jump so much in our evolution at any given time. This leads to a certain kind of "path dependence". Homo sapiens in 2020 are who we are because of homo sapiens in 10,000 BCE. And homo sapiens in 3000 can only follow from homo sapiens in 2020.

In technology, we'll often call this the "law of the adjacent possible." The iPhone wasn't possible in 1930s before computers. We needed information theory, transistors, digital cameras, and GPS before we could build the iPhone.

As another technological metaphor, think of Product-Market Fit (PMFit). PMFit says that a product will only be successful if it meets the needs of the market. Similarly, a given cultural innovation is only possible if it fits our natural biological anchor. We could call this Biological-Cultural Fit, or BCFit.

Now that we've understood Systemic Evolution and BCFit, we can trace these over time to understand how the West got so WEIRD.

III. Apes (Pre-200,000 BCE)

We started as apes. Now we're apes who wear clothes!

As apes, we didn't have the solidified norms and institutions that we've developed today. Those are inventions of homo sapiens.

However, we did have two important biological instincts which provide the anchor for future cultural evolution:

- Polygynous Mating: All ape species besides homo sapiens engage in polygynous mating. All future mating/marriage norms need to be built on our initial anchor of polygyny.

- Kin Altruism: Other ape species engage in kin altruism, where individuals cooperate with close kin in order to increase genetic fitness of close relatives. For example, I may give some extra food to my hungry brother because it increases the chances of his reproduction (and doesn't hurt me too much). Many of our kin-based institutions (like patrilineal clans) are built on the biological anchor of kin altruism.

IV. Early Homo Sapiens (200,000 BCE - 10,000 BCE)

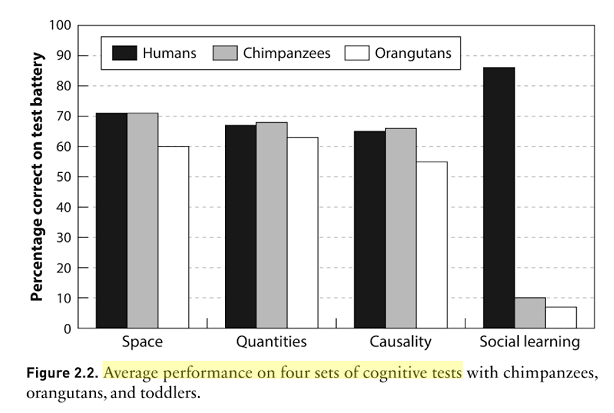

Homo sapiens began to branch off from our ape ancestors. Many of the evolutions around this time were based on social learning and homo sapiens big brains. In fact, our ability to do social learning is what differentiates us from our ape ancestors. In the graph below, we can see how human toddlers compare to chimpanzees and orangutans on a series of cognitive tests. As you can see, humans are roughly equal to apes on tests of physical space, quantity, and causality. But we're much better than apes at social learning.

Homo sapiens brains are optimized for social learning. Instead of being "smart" when we come out of the womb, we start "dumb" but then pick up cultural adaptations extremely quickly. It's what makes us so flexible. Thousands of years ago, we could learn animal tracking from our community. Now, we learn the base-10 counting system.

Genetically, our bodies adapted for new big brains with things like wider hips for females to birth big brains. Culturally, we adapted by developing pair-bonding instincts. These instincts encourage the male-female sexual pair to bond and parent the child during their formative early years.

From a BCFit perspective, pair-bonding instincts were built on the polygynous anchor described above. This means that our (monogamish) pair bonds swim upstream of our polygynous nature. And as we'll soon see, these pair-bonding instincts set the anchor for later marriage norms.

V. Kin-Based Structures in Agrarian Age (10,000 BCE - 500 CE)

Around 10,000 BCE, humans learned how to domesticate animals and plants for farming. This technological evolution led us to larger, more complex societies with proto-institutions like states.

But these institutions were not like the Western institutions we have today, which are built on impersonal trust of strangers. Instead, we built institutions based on our kin instincts. These kin-based institutions had stronger Biological-Cultural Fit. Almost all of these kin-based institutions were based on some form of unilineal or patrilineal descent.

Patrilineal Descent

Patrilineal descent is the cultural adaptation that we should organize our kin structures around our male lineage. In Western societies, children take the father's last name. Or last names themselves will show your lineage: Johnson, Wilson, Anderson, etc.

Why did patrilineal descent show up? Remember, it was evolved, not invented. It's not like some old rich white guy decreed "one must track descent through the father." As it evolved, it needed to outcompete the exist system of bilineal descent (tracking both mother and father lines).

Patrilineal descent outcompeted bilineal descent because it mitigated conflicts of intra-family interest while also providing clear lines of authority. To see the difficulties of bilineal descent, Henrich gives the example of a hunting party:

To see bilineal conflicts, suppose we start with a father who is putting together a defensive party of 10 men to drive some interlopers off their community’s land. The father, Kerry, starts by drafting his two adult sons. This is a nice trio, evolutionarily speaking, since not only are all three closely related but they are also equally related—fathers and sons are genetically related at the same distance as brothers. This parity minimizes conflicts of interest within the trio.

Now, Kerry also recruits his older brother’s two sons, and their sons, who are just old enough to tag along. Still short three men, Kerry recruits his wife’s brother, Chuck, and his two sons.

As you can see, this is a mess of potential conflicts with several possible cleavages. What if Chuck faces a choice between saving one of his own sons in the melee or Kerry’s two nephews? What if Kerry’s nephew gets one of Chuck’s sons killed?

This is why bilineal descent is confusing. Who is on your team? And who do you take instructions from?

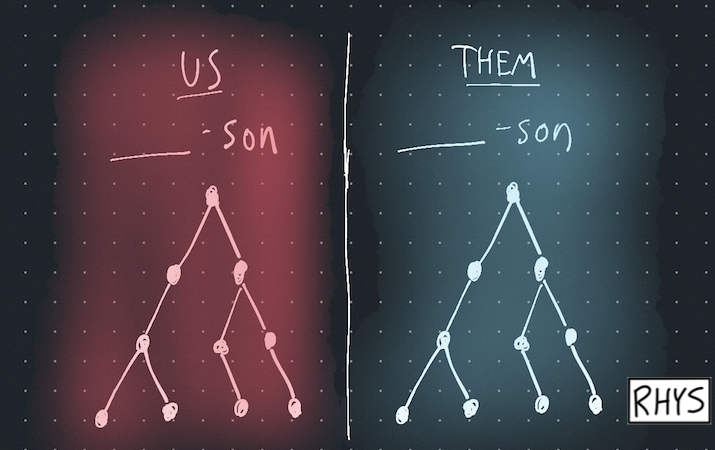

Instead, we can use patrilineal descent to reduce the conflicts of interest. Henrich writes:

To mitigate such conflicts, clans elevate one side of a person’s genealogy over the other and shift the focus of kinship reckoning from one centered on each individual to one centered on a shared ancestor. Thus everyone from the same generation is equally related to a shared ancestor, and everyone has the same set of relatives. This notion is amplified in how these societies label and refer to their relatives in their kinship terminologies. In patrilineal clans, for example, your father’s brother is often also called “father”.

Patrilineal descent simplifies kin structures by turning them into an us vs. them dynamic. It's ____-son vs. ____-son (Anderson vs. Johnson).

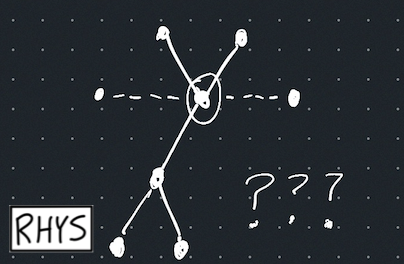

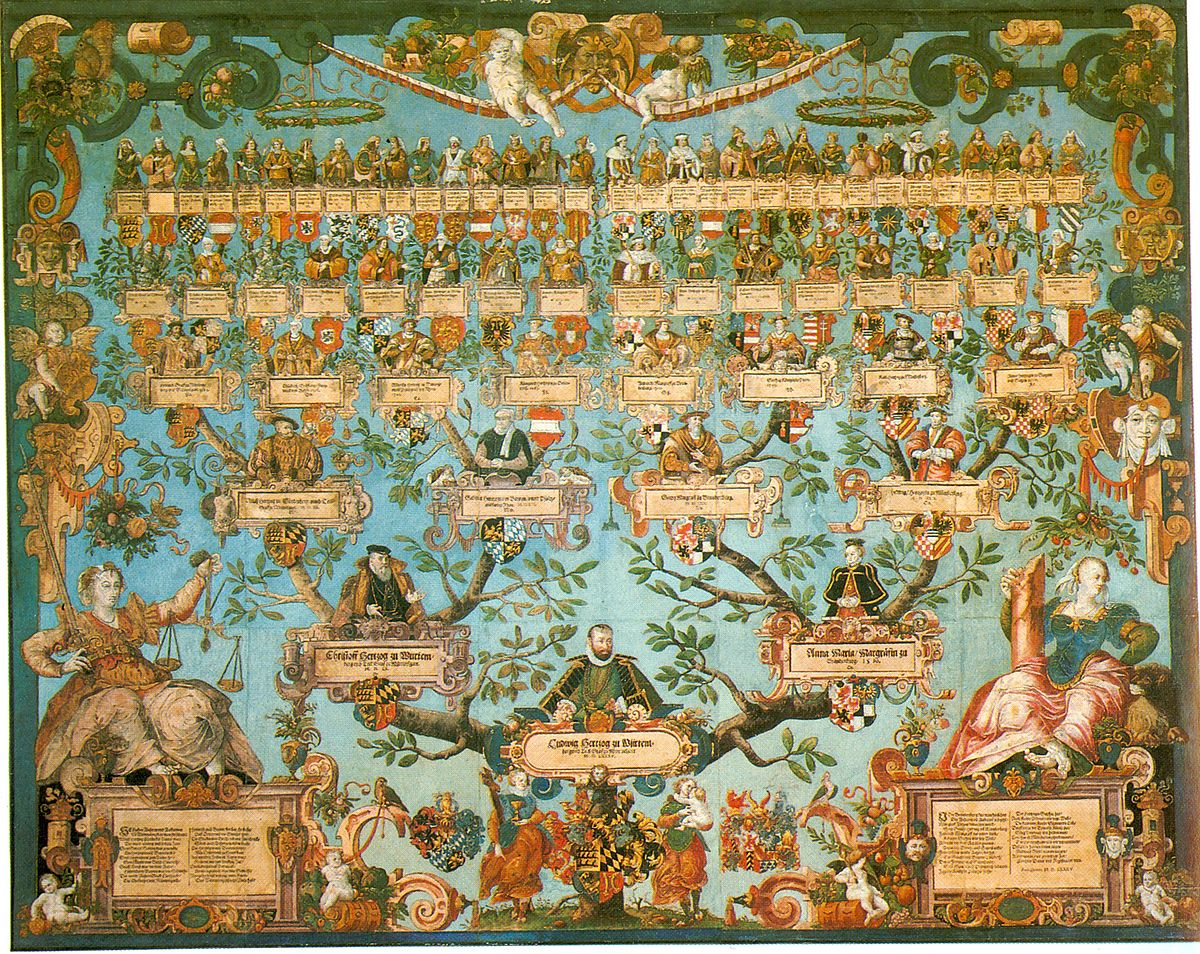

Patrilineal descent birthed a variety of social norms like patrilocal residence (which builds bonds among a father's children), equal-stake inheritance (so all children have aligned financial incentives), incest taboos (which decrease sexual competition within the clan), and arranged marriages (to create a network of alliances). In addition, humans created segmentary lineages—genealogical trees with deep rituals to remember the full clan.

By 500 CE, patrilineal descent had created a world full of strong kin-based clans. These clans had built kin-based norms and institutions on top of our biological tendency towards kin altruism and pair bonding.

However, our modern 2020 society is full of non-kin-based institutions like companies, governments, universities, and organized religion. How did we move away from kin-based institutions? The Catholic Church.

VI. Catholic Church in the Middle Ages (500 CE - 1500 CE)

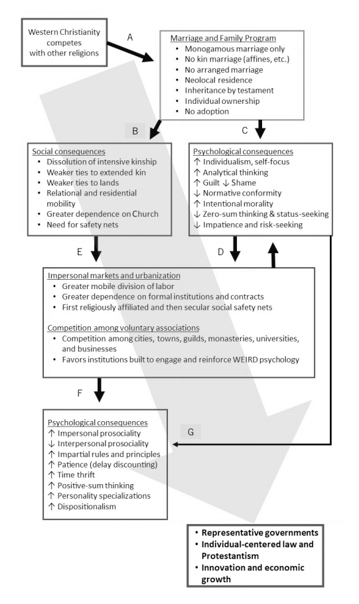

During the Middle Ages, the Catholic Church both: a) broke down existing kin-based institutions and b) built up new non-kin-based institutions. Let's look at each.

VI.A How the Church's Marriage and Family Program (MFP) Broke Kin-Based Institutions

When it formed, Christianity was a hip new kind of religion—one with a moralizing god. Previous religions didn't care much about your personal actions. But Christianity (and Islam, among others) had found a cultural adaptation. By saying "if you do good, God will get you into heaven", these new religions were able to increase impersonal trust between strangers, which allowed larger, more complex societies to form.

As these religions began to spread, they competed with existing kin-based institutions. The Catholic Church competed with kin-based clans by: a) Breaking kin lineages and b) Redirecting financial inheritance from kin to the church.

The Church broke kin lineages by exploiting their Achilles' heel—they must produce heirs every generation. Henrich writes:

A single generation without heirs can mean the end of a venerable lineage. Mathematically, lineages with a few dozen, or even a few hundred, people will eventually fail to produce an adult of the “right” sex. This means that all lineages will eventually find themselves without any members of the inheriting sex. Because of this, cultural evolution has devised various strategies of heirship that involve adoption, polygamy, and remarriage.

The Church exploited this weakness by breaking kin lineages with new rules that constrained adoption, polygamy, and remarriage (their "Marriage and Family Program").

In addition, the Church took money away from kin-based lineages by encouraging inheritance donations to the Church. They even provided a powerful carrot: if you donated to the Church, you were more likely to go to Heaven. And, instead of requiring this during life, you could do it at the end:

Rich people could bequest some or all of their wealth to the poor at the time of their death. This allowed the wealthy to stay rich all their lives, but to still thread the proverbial needle, by giving generously to the poor at their death.

This was a massive moneymaker for the Church. Bequests of land were the most common:

By 900 CE, the Church owned about a third of the cultivated land in western Europe. By the Protestant Reformation in the 16th century, the Church owned half of Germany, and between one-quarter and one-third of England.

Over the course of centuries, the Church slowly broke down kin-based lineages by: a) Destroying the lineages themselves and b) Redirecting their sources of income.

VI.B The Creation of Non-Kin-Based Voluntary Organizations

The Church dismantled kin-based tribes that had previously provided humans with interdependence networks that met our needs of safety and connection. But we still needed to meet those needs. What would take their place?

At this time, a wide variety of non-kin-based voluntary associations began to form in cities: companies, churches, guilds, unions, political parties, and universities. These looked like similar organizations in the East, but were actually built on a new proto-WEIRD foundation. Henrich writes:

While the urban centers of 11th-century Europe may have superficially looked like puny versions of those in China or the Islamic world, they were actually a newly emerging form of social and political organization, ultimately rooted in, and arising from, a different cultural psychology and family organization. Smaller families with greater residential and relational mobility would have nurtured greater psychological individualism, more analytic thinking, less devotion to tradition, stronger desires to expand one’s social network, and greater motivations for equality over relational loyalty.

From 800-1800 the urban population in Europe increased from 5% to 20%. As these cities formed, they created charters and laws to regulate urban behavior. Popular charters (like Magdeburg Law) were copied and remixed throughout Europe.

In these newly booming cities, colleges began to form. The first modern university started in Europe in 1000. 500 years later, there were 50 universities across Europe.

Markets spread as well. Cities applied for grants to hold violence-free markets in their jurisdictions. At the same time, these cities began to attract merchants, traders, lawyers, and other professionals to engage in commerce. They developed lex mercatoria, a set of norms and laws around impersonal exchange.

These voluntary organizations co-evolved with a proto-WEIRD psychology that elevated the individual over the collective, singular objects over holistic relationships, and self-focused guilt over community-given shame. In our previous kin-based culture, it was incredibly important to think of oneself in relationship to the personal contexts around us. But as voluntary associations began to form, it was increasingly important for us to provide a clear individual outward face for others to interact with, like an API.

These voluntary organizations were possible because of both the destruction of old kin-based culture and the incubation of an individualistic proto-WEIRD psychology that made individuals more likely to adopt impersonal associations.

In addition, these voluntary organizations (and their accompanying proto-WEIRD psychology) provided the anchor upon which the Protestant Reformation, Industrial Revolution, and modern nation-states would form.

This is all shown in the feedback loop below. Ape instincts led to the co-evolution of kin-based clans and psychology. Then The Church broke that an led to the co-evolution of WEIRD institutions and psychology.

VII. Protestant Reformation and the Industrial Revolution (1500-2000)

Protestantism sacralized the psychological complex that had been percolating in Europe during the centuries leading up to the Reformation.

In other words, the Protestant Reformation took our proto-WEIRD individualism and codified it into religion:

Embedded deep in Protestantism is the notion that individuals should develop a personal relationship with God. To accomplish this, both men and women needed to read and interpret the Bible for themselves, and not rely primarily on the authority of supposed experts, priests, or institutional authorities like the Church. This principle is known as sola scriptura.

As Max Weber argues in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, this Protestant ethic led directly to the Industrial Revolution and modern capitalism.

But was this the only explanation for why Europe was the center of the Industrial Revolution? No. Henrich writes:

Proposed explanations for “Why Europe?” emphasize the development of representative governments, the rise of impersonal commerce, the discovery of the Americas, the availability of English coal, the length of European coastlines, the brilliance of Enlightenment thinkers, the intensity of European warfare, the price of British labor, and the development of a culture of science.

Henrich believes it was our proto-WEIRD psychology that underpinned each of these explanations:

I suspect that all of these factors may have played some role, even if minor in some cases; but, what’s missing is an understanding of the psychological differences that began developing in some European populations in the wake of the Church’s dissolution of Europe’s kin-based institutions.

The cultural evolution of psychology is the dark matter that flows behind the scenes throughout history.

Let's look at a few manifestations of this psychological WEIRD dark matter: a market mindset, individual rights, and scientific practices.

VII.A Doux Commerce as Domesticated Intergroup Competition

Capitalism rose with a market psychology that Henrich touches on. (And, imo, is most clearly explained in Albert Hirschman's The Passions and the Interests: Political Arguments for Capitalism Before Its Triumph.) The idea is one of domesticated intergroup competition. Instead of killing each other in competition, we just beat each other in the market.

This mindset (of gentle commerce, or doux commerce) was spearheaded by various thinkers at the time:

Commerce is a cure for the most destructive prejudices; for it is almost a general rule that wherever manners are gentle there is commerce; and wherever there is commerce, manners are gentle.

—Montesquieu (1749)

Commerce is a pacific system, operating to cordialise mankind, by rendering Nations, as well as individuals, useful to each other...The invention of commerce...is the greatest approach toward universal civilization that has yet been made by any means not immediately flowing from moral principles.

—Thomas Paine (1792)

VII.B Individual Rights and Democracy

In addition, our proto-WEIRD individualism also led to the formation of modern law and especially the concept of individual rights. Henrich again:

The Declaration of Independence asserts, “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

If the idea that people are endowed with such abstract properties makes sense to you, then you are at least a little WEIRD.

By contrast, from the perspective of most human communities, the notion that each person has inherent rights or privileges disconnected from their social relationships or heritage is not self-evident.

And from a scientific perspective, no “rights” have yet been detected hiding in our DNA or elsewhere. This idea sells because it appeals to a particular cultural psychology.

Individual rights gave individuals power they had never had before. In addition, democracy itself began to empower the general populace. Before democracy, only gods or lineage gave one legitimacy. Now, the people themselves were seen as a source of legitimacy. (Crazy!)

VII.C Individualistic Science and the Collective Brain

With the rise of universities, European science was beginning to blossom. These new European scientists were a bit different though—they had proto-WEIRD individualism. Instead of respecting their scientific elders, they new actively pushed back against them. This led to paradigm shifts like Copernicus' discovery of heliocentrism in 1543.

In fact, the very notion of "discovery" was discovered at this time. The word itself first appears in European languages around this time: Portuguese in 1484, Italian in 1504, etc.

In addition, scientists began to associate discoveries with individuals. Henrich writes:

Our commonsensical inclination to associate inventions with their inventors has been historically and cross-culturally rare. This shift has been marked by the growth of eponymy in the naming of new lands (“America”), scientific laws (“Boyle’s Law”), ways of thinking (“Newtonian”), anatomical parts (“fallopian tubes”), and much more. After about 1600, Europeans even began to relabel ancient insights and inventions based on their purported founders or discoverers. “Pythagoras’s theorem,” for example, had been called the “Dulcarnon” (a word derived from an Arabic phrase for “two-horned,” which described Pythagoras’s accompanying diagram)."

Ideas themselves could now be stolen:

"Marking this in English, words for “plagiarism” first began to spread in the 16th century, following the introduction in 1598 of the word “plagiary,” which derives from the Latin word for kidnapping."

With the rise of the printing press and knowledge societies, these new individualistic scientists began to operate as a collective brain. Henrich again:

The Cistercian Order, in particular, built a sprawling network of monastery-factories that deployed the latest techniques for grinding wheat, casting iron, tanning hides, fulling cloth, and cultivating grapes. At mandatory annual meetings, hundreds of Cistercian abbots shared their best technical, industrial, and agricultural practices with the entire order. This essentially threaded Europe’s collective brain with Cistercian nerves, pulsing the latest technical advances out to even the most remote monasteries."

These examples—individual rights, doux commerce, and an individual collective brain—are all manifestations of this new individualistic WEIRD psychology. Can we get closer though? To measure WEIRDness itself?

The most direct way to measure this psychology is through the BIG-5 personality test, which is a scientifically-backed set of 5 traits that all individuals can be measured by. You can remember them with the mnemonic OCEAN: openness to experience, conscientiousness, extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism.

So, we'd expect WEIRD folks to look different than non-WEIRD folks, right? Like maybe Western folks are more extraverted?

Wrong! In fact, non-WEIRD folks don't even register on the same personality test—they have a completely different set of personality dimensions. For example, some anthropologists studied the remote Tsimané people. Their society is built differently than Western society (i.e. no impersonal institutions). And therefore, the personality types that one can "be" in their society are different. Instead, their personality types mostly group along two clusters: pro-sociality and industriousness. In rural Tsimané society, there's no evolutionary niche for 5-dimensions of personality to emerge. While in a more urban culture, there's room for occupational diversity.

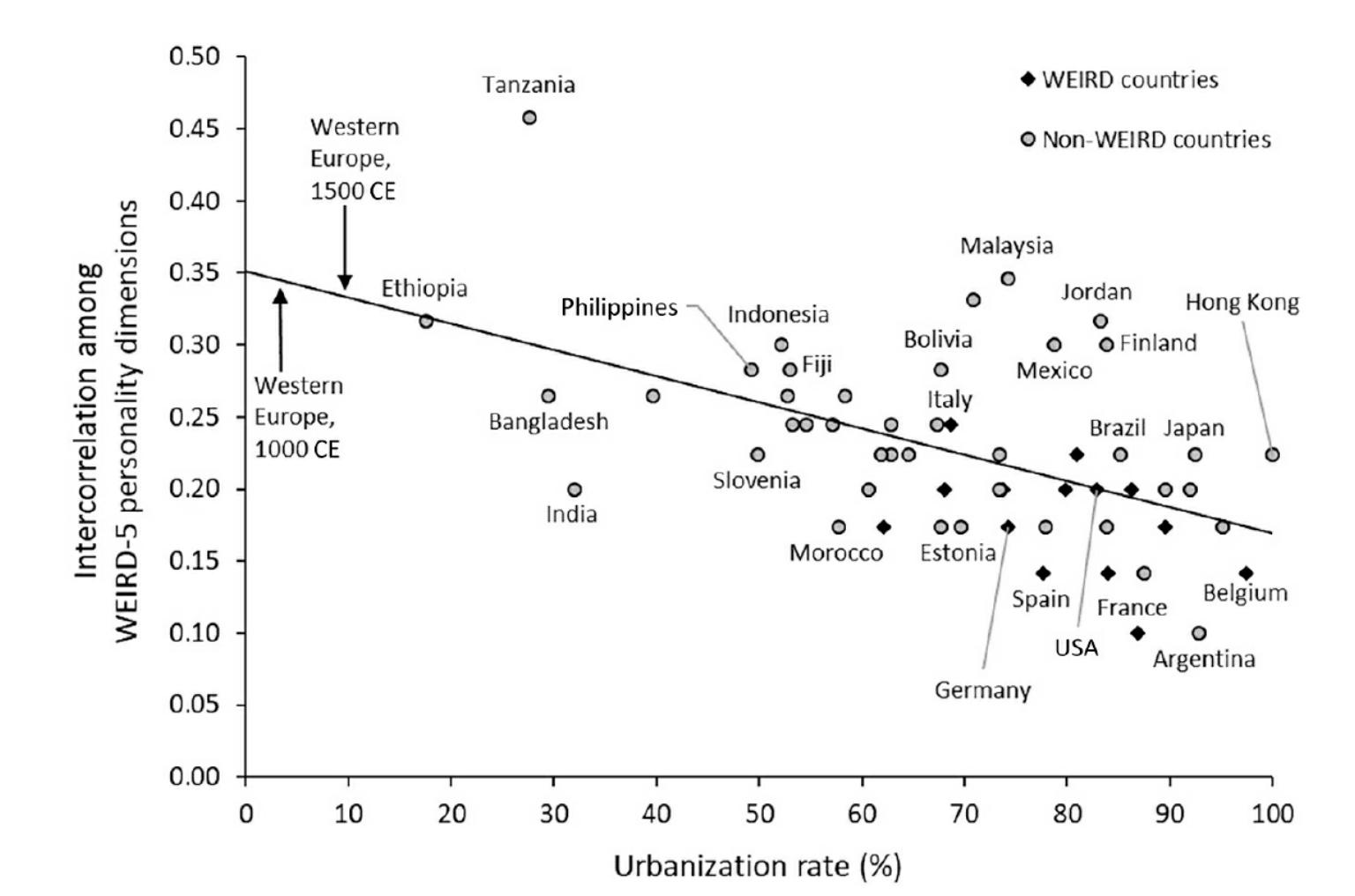

We can see this statistically by looking at the intercorrelation among BIG-5 traits. In theory, the traits should be orthogonal to each other. For example, in the USA, there's only a 0.10 correlation between traits. But in a non-WEIRD country like Tanzania, there's nearly a 0.50 correlation between traits!

The graph below (from Henrich) shows how urbanization rate correlates with BIG-5 intercorrelation.

This is all to say: BIG-5 personality traits are just a manifestation of WEIRD psychology and parallel co-evolution of WEIRD impersonal institutions. It's not the BIG-5, it's the WEIRD-5.

VIII. Conclusion

In today's article, we looked at why the West is so WEIRDly individualistic: The Church broke down kin-based structures which created space for impersonal institutions that highlighted the individual. These new institutions became embedded in people as a WEIRD individualistic psychology. (Which then led to even more impersonal institutions.) Here is how Henrich explains the whole trajectory:

But I'd represent it as this Loopy. Ape instincts led to the co-evolution of kin-based clans and psychology. Then The Church broke that and led to the co-evolution of WEIRD institutions and psychology.

In the next part of this series, I'll show how we can use Henrich's model to positively shape the future. Until then!

Thanks to my generous patrons ❤️

Todd Youngblood, Jim Rutt, Zoe Harris, Yancey Strickler, Jacob Zax, David Ernst, Jonny Dubowsky, Brian Crain, Matt Lindmark, Colin Wielga, Samuel Jonas, Andy Cochrane, Malcolm Ocean, Ryan Martens, John Lindmark, Collin Brown, Ref Lindmark, James Waugh, Mark Moore, Matt Daley, Coury Ditch, Brayton Williams, Jeff Snyder, Mike Goldin, Chris Edmonds, Peter Rogers, Darrell Duane, Denise Beighley, Scott Levi, Harry Lindmark, Simon de la Rouviere, and Katie Powell.