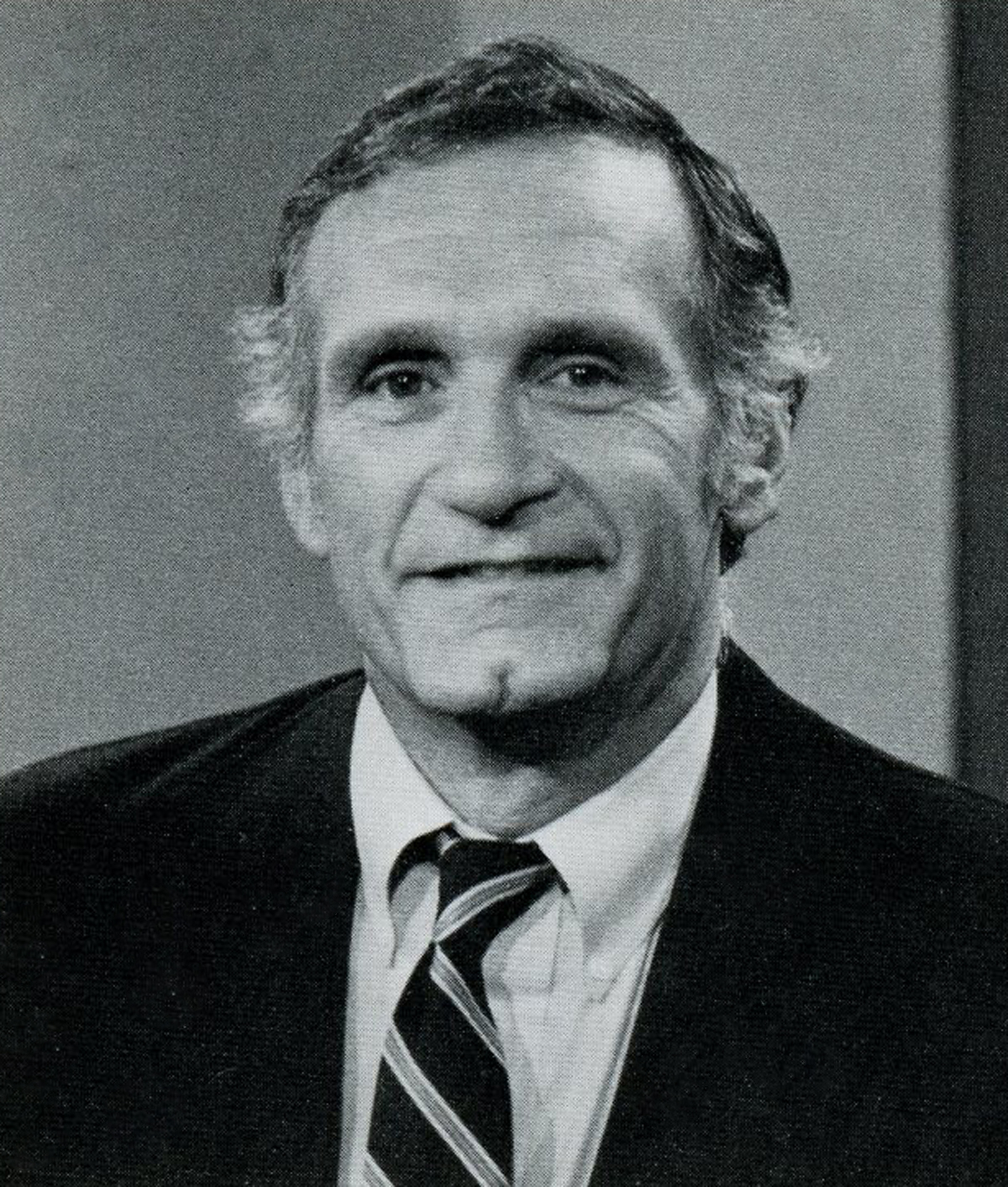

Remembering James Carse

James Carse, the author of Finite and Infinite Games, passed away last week. I want to remember his legacy by revisiting his book and the impact it had on us.

I have three points:

I. Infinite Games Provided An Oasis for Exiles Uncomfortable with the Status Quo

II. Carse Would Want Us To Care For Each Other and The Future

III. Death Itself Manifests a Paradox of Finite and Infinite Games

I. Infinite Games Provided An Oasis for Exiles Uncomfortable with the Status Quo

Finite and Infinite Games is more poetry than book. At first, the prose is jarring. But as you learn about infinite games, you realize the words themselves are a manifestation of the infinite games mindset.

So what is this mindset? What is the difference between finite and infinite games?

A finite game is played for the purpose of winning, an infinite game for the purpose of continuing the play.

This distinction is confusing because we only know one side of it—the world is full of finite games. It's difficult to even imagine an infinite one.

When explaining infinite games in-person, I like to play an example infinite game:

Me: The game is called The Blue Game. There are two players, you and me. The goal of the game is to say the word "blue". We play best-of-three. You can start.

Them: Blue.

Me: Nice! You're winning 1-0. Now my turn to start. Red.

Them: Blue.

Me: You won 2-0. The game is over.

And then we play another round, where we play an infinite game that begins to taste like improv. We both say many colors, just to keep playing the game: red, yellow, orange, maroon.

The goal of finite games is to win. The goal of infinite games is to keep playing. Why does this distinction speak to us?

I want to give a personal story for why infinite games resonated with me. I think it's similar to one that many of us share.

Like Carse, I was born into a world of win-lose finite games, especially in sports. Carse himself has spoken about playing competitive sports during his childhood, but how they always rubbed him the wrong way—too much anger and othering of the opposing team. I also grew up playing competitive sports, but it never sat well with my gut. Coaches and players and parents were always yelling at each other. The high-five line at the end often felt stale.

In high school, I found Ultimate Frisbee, which was closer to an infinite game (though I didn't have that language yet). There were no referees so the players had to self-referee themselves, which created a sense of mutual accountability. And when I played in college, hanging with the opposing team afterwards was as much a part of the interaction as the game itself. Sure, there were winners and losers. But we all knew it was just frisbee. The main goal of the game was to keep the quirky sport alive, not to beat the other team. And, we were all exiles from the world of competitive sports. We had left the land of ESPN and found a community of weirdos who thought about sports in a similar different way.

Like with frisbee, Carse's infinite games defined a different way to play. Infinite games showed us we're not crazy, that others thought like this too. That maybe, our our gut was right, and that there's a name for our instinct—an infinite game. It speaks to us the same way Burning Man, prison abolition, Bitcoin, or [insert crazy idea here] speaks to us—as a completely new set of default assumptions. The idea that, yes, there is an alternative, an exit. That we can think about what defines the game, rather than just play within its definitions:

Finite players play within boundaries; infinite players play with boundaries.

Carse showed us a new way of perceiving the world. An oasis of thought inhabited by a community of exiled nomads to co-perceive with. It's amazing how powerful a simple "in-"(finite) prefix can be. We're all grateful for that.

But what now? How can we honor Carse and his book?

II. Carse Would Want Us To Care For Each Other and The Future

I think Carse would say many things, but I want to emphasize two ideas here:

- Help others play infinite games

- Understand yourself so you can play more authentically

Let's look at each.

First off, Carse wanted to help others play infinite games. He writes:

The rules of an infinite game are changed to prevent anyone from winning the game and to bring as many persons as possible into the play.

If the game is life, how can we help more people play?

We can help others reach a level of comfort where they can play infinite games. It's difficult to play if you're of the 750 million people still living under $2 per day. Also, we can ensure the game goes on. Pandemics, the climate crisis, and nuclear tensions can all provide a finite ending to our game. To ensure the human experiment continues, we need to think long-term.

These two points are easy—care about each other and future generations. And yet, they are hard too! In fact, they become more difficult as infinite gamers reach a level of comfort where they can "coast" as they play. Don't fall for this trap! Try to conceive of an infinite game where you're relentlessly trying to help more folks play.

I believe Carse's second piece of advice would be to understand yourself to play an infinite game. If you're not playing from an authentic and confident place, then you're playing for the external praise of others. This automatically turns your playing into win-lose dynamics—winning is determined based on where the praise is showered. Carse spoke about this in a recent interview with The Stoa:

Find things in yourself that are a genuine act—something that comes from your personal center and can't be categorized. Something that's you, deep down. When you act from that, what I call original acting, we move from ourselves outward. But the world doesn't like this, so conflicts develop. Prepare yourself to not always find a welcome audience. There are a lot of folks that don't want you to be who you are.

Become comfortable in your own skin. Only then can you embody co-partnership in infinite play. To play an infinite game is to be in relationship with yourself, the other, and the relationship between the two.

III. Death Itself Manifests a Paradox of Finite and Infinite Games

Carse's passing is a reminder that death is the terminal move in our finite game of life. Even Carse could not escape that.

And yet, we can reframe it as infinite by continuing to build on his ideas. Carse touched on a similar idea in his final interview before his death. He was re-reading the dialogues of Greek philosophers and this passage from Socrates stood out to him:

Socrates said, "I have taken up the art of intellectual midwifery. I help people bring ideas into birth. They're not well-conceived, I need to help them. On the other hand, I can't do it myself. I need you to bring my wisdom and knowledge into birth."

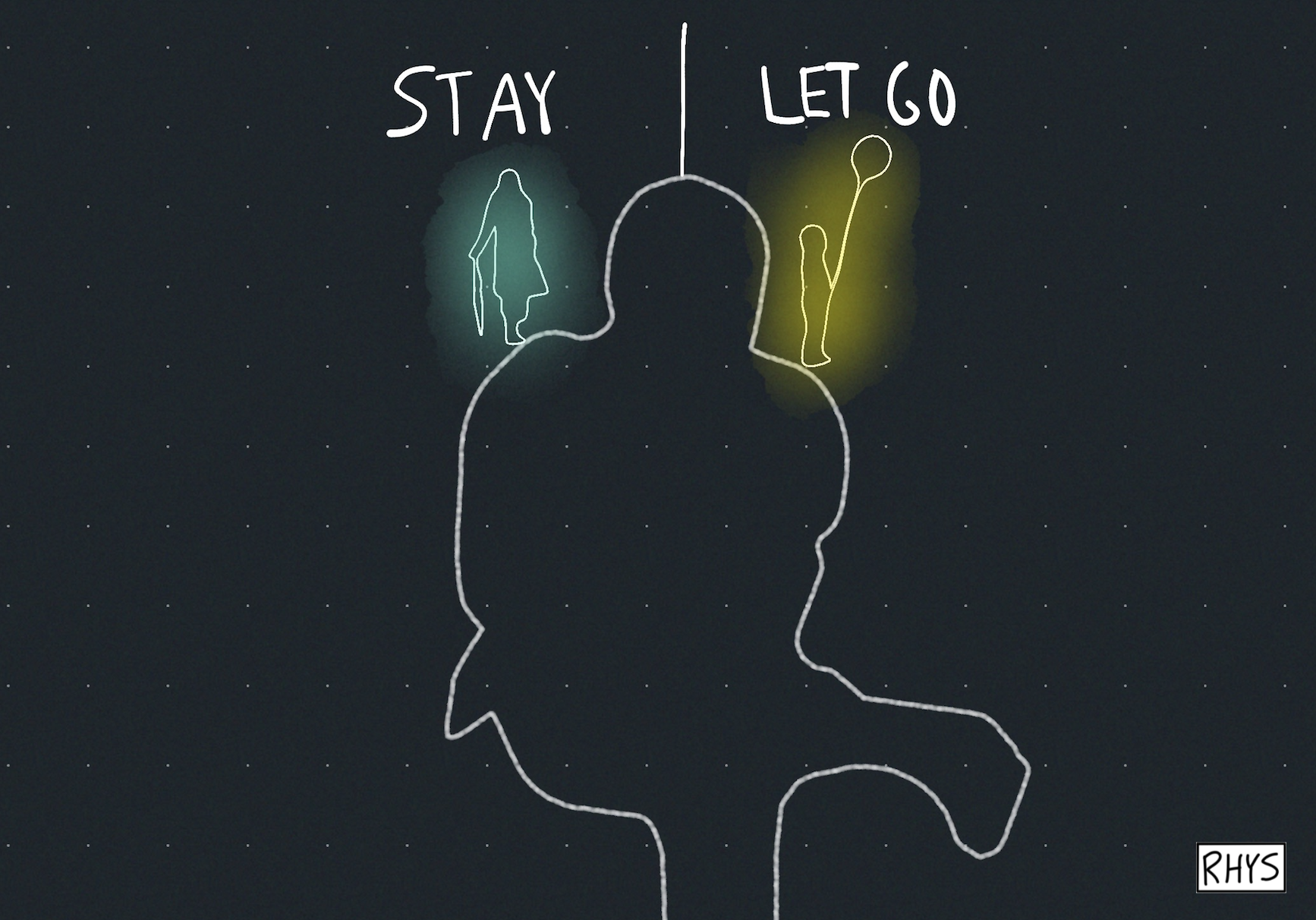

Carse provided intellectual midwifery for all of us with Finite and Infinite Games. It's time for us to birth those ideas into being.

Indeed, this is one of the primary paradoxes of death—that we should keep Carse with us, but also let him go.

Here are some nice quotes on how to keep Carse with us:

"They say you die twice. One time when you stop breathing and a second time, a bit later on, when somebody says your name for the last time." — Banksy

"No one is actually dead until the ripples they cause in the world die away." — Terry Pratchett

"What we have once enjoyed deeply we can never lose. All that we love deeply becomes a part of us." — Helen Keller

And here's a poem from Mary Oliver, "In Blackwater Woods", which describes the opposite process of letting go:

you must be able to do three things:

to love what is mortal;

to hold it against your bones knowing your own life depends on it;

and, when the time comes to let it go, to let it go.

RIP James Carse