When Should Law Forgive?

“Forgiveness does not change the past, but it does enlarge the future.”

— Paul Boese

To forgive or not forgive? That is the question.

Should we forgive student debt, rent during COVID, and The Other Side for supporting their candidate? These are difficult questions to answer.

Martha Minow, Obama's favorite law professor at Harvard, has written multiple books on forgiveness. Her most recent book is "When Should Law Forgive?"

It outlines how we can think about forgiveness. I want to cover four main points:

I. What is forgiveness?

II. How can we balance forgiveness and accountability?

III. How do laws and norms shape forgiveness?

IV. What role does individualism play in forgiveness?

Overall, Minow's perspective argues for more forgiveness. Her first sentence is:

Ours is an unforgiving age, an age of resentment. The supply of forgiveness is deficient.

Let's understand her perspective better.

I. What is forgiveness?

Minow defines forgiveness as:

a conscious, deliberate decision to forgo rightful grounds for grievance against those who have committed a wrong.

This has never been seen on the internet, but I'm told it exists IRL.

The key part of this definition is that it requires a wrong to occur. If you catch your brother stealing your favorite spotted cow, but you forgive him, that's forgiveness. But if you learn that he was framed by your mother and didn't actually steal your cow, that's not forgiveness. He did nothing wrong.

Using DNA testing to prove the innocence of a death row inmate is not forgiveness. Deciding not to prosecute them, even if they're guilty, is.

Claiming that students aren't responsible for their debt isn't forgiveness. That's just putting the blame on skyrocketing college prices and stagnating wages. But saying students are responsible for their debt and yet still absolving them is forgiveness.

Forgiveness is a relationship to a wrong, not a right.

In addition, Minow highlights that forgiveness doesn't just help the guilty; it is for the forgiver as well. Minow quotes Jodi Picoult:

“Forgiving isn’t something you do for someone else. It’s something you do for yourself.

It’s saying, ‘You’re not important enough to have a stranglehold on me.’ It’s saying, ‘You don’t get to trap me in the past. I am worthy of a future.’ ”

Forgiveness acknowledges a wrong and gives both parties a chance for a better future.

II. How can we balance forgiveness and accountability?

This definition of forgiveness naturally leads to the question—why should we forgive if someone has done a wrong? If I can steal without any punishment, what is to stop me from stealing? Am I accountable to my actions?

There's no right answer here. There are times for forgiveness and times for accountability. We can only be in relationship to this relationship (between forgiveness and accountability).

1. Accountability can help develop moral agency

To learn about this balance, Minow explores whether we should forgive child soldiers for murder. On one side, they don't need forgiveness, because they didn't commit any wrong—they were just innocent kids! Minow writes:

Ironically, viewing child soldiers as innocent victims puts forgiving them beyond reach, because forgiveness is only for those who have committed a wrong.

But on the other side, they clearly did a wrong (e.g. murder) and need to come to terms with their personal responsibility. Minow provides the provocative perspective that holding children accountable is helpful for the children themselves. She writes:

Child soldiers should be seen as individuals struggling for meaning and needing to maintain or create a sense of their own moral agency, including recognition of past wrongdoing. Many child soldiers may have a strong sense of self, linked to their survival and resilience. Others may grapple with ambivalence and shame.

Imposing no consequences for the harms committed by former child soldiers may impair development over time of their own identities as moral agents.

As Emmanuel Jal, a child soldier turned rapper, sings:

“I’m in another war. This time it’s my soul that I’m fighting for.”

Ishmael Beah, author of the 2007 best-seller A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier, gives his perspective:

"What I think is you forgive and you forget so you can transform your experiences, not necessarily forget them but transform them, so that they don’t haunt you or handicap you or kill you. Rather, you transform them so they can remind you, so that this doesn’t happen again."

Accountability helps child soldiers develop moral agency. We should hold them accountable, while recognizing they were immature children put into a horrifying situation.

2. Accountability (and forgiveness) should take proportionality into account

Another key to balancing accountability and forgiveness is making sure the punishment (or forgiveness) is proportional to the wrong.

The most famous example of proportionality is "an eye for an eye". It has been used throughout time as a way to dispel the positive feedback loop of escalating responses. If I steal $1 from you, you can steal a $1 back. But if you steal $2 in return, then I steal $4, it gets out of hand quickly.

It ain't: An eye for an ear for an arm for a leg for a body.

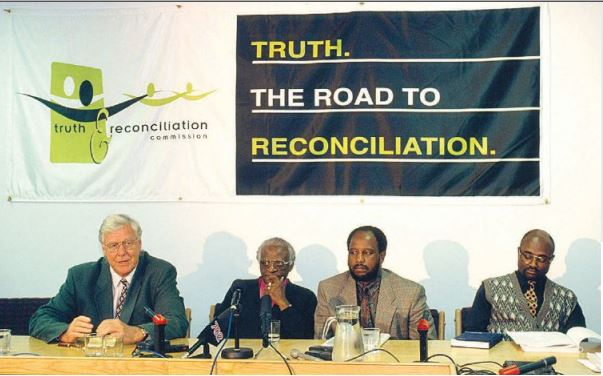

Proportionality was a crucial part of forgiveness at the end of apartheid in South Africa. In 1996, the country set up a Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to hear and forgive the wrongs of apartheid. But, as Minow notes, you could only receive amnesty proportional to your wrong:

Over the three years of its operation, the TRC invited victims to tell their stories. It also invited perpetrators to apply for amnesty, conditioned on their showing that their actions had been limited to a political rather than a personal goal, and that the means they used were proportional to that political goal.

I love how TRC's slogan emphasizes both truth (the wrong) and reconciliation (the forgiveness).

Balancing forgiveness and accountability is no easy task. Proportionality is a crucial first step.

III. How do laws and norms shape forgiveness?

But wait a second. How does something with institutional backing like the TRC get set up? How do we go from personal forgiveness to institutionalized law? Minow notes this tension:

Forgiveness operates in the interpersonal realm; the legal system depends upon impersonal processes.

1. Three ways law can forgive

Minow outlines three ways that law can forgive:

First, judges and legislatures can enact categorical treatments of wrongdoing that alter or otherwise reduce consequences.

An example of this is when Reagan granted amnesty and a path towards citizenship to 3 million undocumented immigrants.

Second, legal systems can enable and support the exercise of discretion by legal officials toward leniency rather than punitiveness. Some written and unwritten norms work in the other direction, such as compelling parking meter officers to issue quotas of parking tickets.

Unfortunately, I don't know any examples that encourage discretion towards leniency. I only know things like mandatory sentencing and three-strikes laws that encourage punitiveness.

I like to think of these incentives as similar to the forest management rules in the United States. Fires burning down houses is legible. Firefighters are incentivized to stop fires instead of doing controlled burns. Fires must be stopped. Discretion is not on the table.

Third, law—formal rules, legal institutions, and the people who implement them—influences whether individuals are likely to express forgiveness.

This final point is a general one. It says that impersonal law impacts personal forgiveness. With the TRC, some victims were less likely to personally forgive because they felt the TRC gave too much amnesty to perpetrators.

I like to think of Minow's three points as moving from specific to general:

- Law can directly forgive

- Law can incentivize discretion towards forgiveness (or not)

- The two points above change how individuals personally forgive

2. When law forgives, does that undermine the law itself?

As noted in the last point above, law can make individuals more or less likely to personally forgive. If law forgives too much, it undermines itself. It's seen as too mutable. Minow writes:

If courts forgo warranted legal consequences in favor of individualized forgiveness by legal actors, and if they use law to support individual forgiveness, they could well risk undermining the law’s predictability, adherence to rules, deterrence, fairness, and objectivity.

This is connected to the idea of accountability. If your brother can steal your cow and not be punished, what is stopping him from doing it again? What if all cow stealers are not punished? Then the law itself comes under scrutiny and loses its legitimacy.

On the flip side, if law doesn't forgive enough, it undermines itself. It's seen as too rigid. Minow quotes from Justice Anthony Kennedy:

"A people confident in its laws and institutions should not be ashamed of mercy."

When the government has legitimacy and the people's trust, it is ok to forgive because the people aren't worried about the law's consistency in general.

Paradoxically, forgiveness works only if there is punishment. Flexibility is a sign of consistency.

3. Do we need law if we have strong morals?

Perhaps there is a future world where our morals are strong enough that we don't need law. To some extent, that is true already. We have a lot less beheadings per capita than in the dark ages. (Thank god.)

Law can both precede morality and follow it. In the 1800s, there was an emerging abolitionist morality that law against slavery eventually codified. And also, those laws "forced" the new morality onto folks who didn't believe it yet.

Today, we don't need those slavery laws as much. Our morality and norms strongly prohibit slavery, so the law doesn't need to step in.

Minow makes this point by quoting Grant Gilmore:

“In heaven there will be no law, and the lion shall lie down with the lamb...In Hell there will be nothing but law, and due process will be meticulously observed...

Law reflects the moral worth of a society, and more law is needed in societies that are less just."

4. Norms: Just because law forgives doesn't mean your family will

Sometimes, law will forgive, but the community norms won't. As an example, Minow highlights how child soliders and sex slaves come home to stigma, even if the law has forgiven them.

In this section, we looked at how law interacts with forgiveness.

- Law can directly or indirectly forgive

- Which changes how individuals forgive, and the legitimacy of law itself

- Paradoxically, the stronger institutions and morals we have, the less law is needed and the more it can forgive

- But law isn't the only mechanism of forgiveness—norms and stigma play a role

IV. What role does individualism play in forgiveness?

Modern rule of law has been incubated in individualistic WEIRD societies. Paradoxically, the individualism of WEIRD psychology co-evolved with impersonal institutions like rule of law. Presenting a clear individualized API is crucial for interacting with impersonal institutions like law. The law needs you to be legible, not a messy web of contextual relationships.

Individualism makes us think that people bear personal responsibility for their wrong. People in WEIRD countries more often believe the fundamental attribution error, a cognitive bias which states that my failure is the result of the situation, but your failure is because you're a bad person. I'm late because of traffic. You're late because you're lazy.

This error mediates a necessary condition of forgiveness, whether someone did a wrong in the first place. I don't need to forgive you for being late if is actually wasn't your fault.

Minow highlights how forgiveness processes, like bankruptcy, can forgive by acknowledging context instead of just blaming the individual:

Discharging debt through a bankruptcy process addresses larger patterns: It brings together multiple parties who look to the future while remedying broken promises. It not only acknowledges and adjusts the behavior of the immediate parties, the debtor and creditors, but also implicates the larger credit market and even the bad luck that influences debt.

Seeing wrongs as part of a larger system is a way to bring proportionality into the forgiveness process. Instead of blaming someone for 100% of their debt, and then trying to forgive them for it, we can blame them for 25% of their debt, acknowledge the larger 75% context, and then forgive them for their part in it.

In addition, individualism can provide too narrow a scope for an individual's healing process. Minow writes:

Ironically, the Western conception of the primacy of the individual may neglect the needs of particular individuals involved. Western ideas of the individual focus on PTSD and treatment, but a former child soldier’s actual stress may result not from past trauma but from current living circumstances, fears of community retaliation, difficulties in family and community relationships, or worries about the future.

WEIRD countries don't like the illegibility of complex community relationships. It's easier to focus on the individual—whether to blame them or to forgive them.

WEIRD individualism shows up in one final way—with the labels we use for offender and victim. It's hard to be forgiven if you're always seen as an offender. This is why there's recently been a push for person-first language. Minow notes:

Some restorative justice efforts resist the labels offender and victim because they provide little room for growth and social reconstruction; instead, they deploy terms like person harmed and person who caused harm.

There's no right answer here between identity-first language and person-first language. But if you come from a WEIRD country, you're almost certainly overindexed on individualism and the fundamental attribution error. You should strive to see people as a function of their environment but with the capacity to change.

In conclusion, we looked at:

I. What is forgiveness?

II. How can we balance forgiveness and accountability?

III. How do laws and norms shape forgiveness?

IV. What role does individualism play in forgiveness?

More than anything though, Minow's book shows us the tensions inherent in forgiveness:

- Forgiveness vs. Accountability

- Consistent vs. flexible law

- Attributing wrongs to people vs. the system

Forgiveness is messy, but healing is necessary. We should strive to create space and time for it.